The Case Against Tracy Flick and Other Musings About the Film Election:

A Review, Analysis, and Commentary of a Lesser-Known Masterpiece

Author’s note: it is hoped all readers will have watched this phenomenal film. This essay contains many spoilers. Those who have not yet seen this film are urged to do so, whether they decide to read this analysis and review or not.

Election (1999) remains one of my very favorite films of all time. If I were in a context or situation where I could only name one of my favorite films as my very favorite, I would probably nominate Election, not just because it is a cinematic masterpiece, but because it is a unique selection that is somewhat less obvious than those cinematic greats1 that routinely make various lists of “the greatest films of all time.” While the film is not nearly as well known and celebrated as it ought to be, (it is surprising how many have not seen it), it is not completely buried in obscurity, either. Tracy Flick has some currency in modern discourse, as she has been compared to both Hillary Clinton and Sarah Palin. The film offers profound psychological insights, as well as important, thoughtful commentary on education in the United States and, by extension, American society at large. The film offers a particularly biting portrayal of teachers in public schools, while also revealing certain peculiarities and flaws in American notions of meritocracy. And the film does all of this with a distinctive, understated sense of humor all its own.

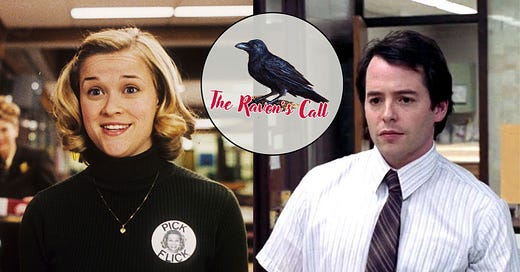

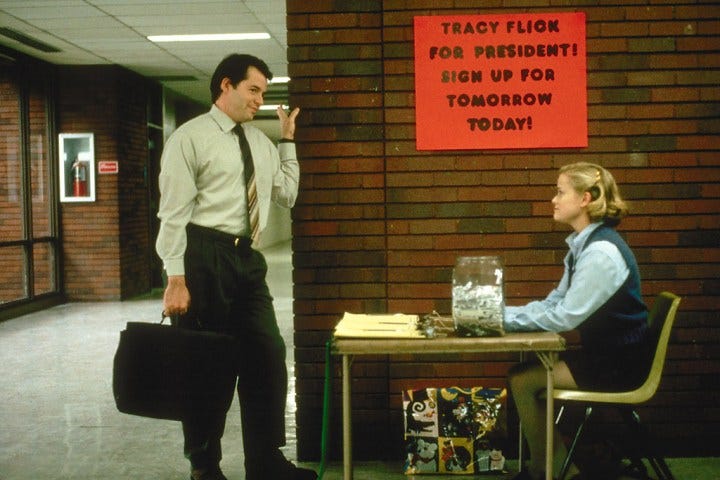

Directed by Alexander Payne, the film centers around Tracy Flick, an ambitious, over-achieving student who is running for class president unopposed, that is until Mr. McAllister, played by Matthew Broderick, decides she needs to be stopped, and encourages Paul Metzler to run against her. Paul was the star quarterback for the school’s football team earlier that year, until he suffered a crippling leg injury in a ski accident. Other circumstances in turn compel his rebellious, alienated younger sister, Tammy Metzler, to run as well. Chaos and pandemonium ensue, including an iconoclastic speech by the second candidate “in the Metzler clan” skewering the whole sordid charade of student government. By the end of the film, Flick and other intervening circumstances bring down McAllister’s tenure at Carver High as well as his marriage. He is soon thereafter driven out of Omaha, Nebraska, where most of the film takes place.

A Knock on Teachers, and the Case Against Tracy Flick

When the film was first released, and in the first few years immediately thereafter, audiences were generally split on whether they sided with McAllister, Flick, or regarded every party with more or less comparable levels of disdain and disapproval, although those favoring Flick seemed to be a minority. Continued feminist influence, such as seen in the #metoo movement as well as heightened (and legitimate) public concern over teacher-student sex scandals have shifted the balance in favor of Flick, at least in some circles. In this retrospective review in The New York Times, A.O. Scott recounts that he was decidedly against Tracy Flick when he first viewed the film so many years ago, but has since decided she was entirely innocent and should be seen as the unequivocal protagonist of the film. Quite remarkably, he even deems her to be the “heroine” of the film. Another particularly obnoxious review written by one Daniel Joyaux likens Tracy Flick to every modern avatar of feminism, including Hilary Clinton, Kamala Harris, and Taylor Swift, and even suggests the film is “the best test for media literacy,”2 with anyone who fails to express unmitigated admiration for Flick to engage in “wrong readings”3 of the film.

This author remains a steadfast partisan for the Mr. McAllister side of the struggle, or against Tracy Flick to be more precise. This position is in tension with any honest appraisal with Jim McAllister, however, as close consideration and analysis of the narrative and its themes reveals him to be a very flawed, even pathetic man. He is not a character that anyone should admire or sympathize with, at least not in most circumstances.

One of the most overt themes of Election, and one of the features that makes it both so biting and insightful, is how it skewers teachers in American public education, and does so in a variety of ways. The portrayal of Dave Novotny, a friend and colleague of McAllister, is the most immediate instance of this. This is demonstrated in his awful rendition of “Foxy Lady” in the garage as McAllister describes his friendship, before the sexual impropriety with Flick had occurred. That flashback scene is part of a montage depicting Novotny’s seduction (some might say grooming) of Flick that began earlier in her junior year (the same academic year the election and most events in the film take place), which quickly led to an illicit sexual relationship, as well as infidelity to his wife who just gave birth to a newborn such wrong-doing necessarily entails. Novotny foolishly wrote love letters to Flick, which her mother quickly discovered. Rather than go to jail, “he moved back home with his parents in Wisconsin” doing menial retail work. Educators are further portrayed in a negative light by the way the school principal, Dr Hendricks, retaliates against Tammy Metzler, simply because he and other staff did not like what she said, giving her a three-day suspension. Astute viewers will note Hendrick’s office is a windowless room featuring concrete construction blocks, with oil paintings hanging off them.

Jim McAllister however is arguably the principal vehicle by which Payne portrays teachers in such an overtly negative light. That unflattering portrayal includes a bad hair-cut and ill-fitting, ugly clothes, notably a lot of cheap short-sleeve button-down shirts and clashing ties, doubtlessly purchased at JC Penney or other low-end department stores and clothiers. The opening scene shows him navigating a chain link cage after his morning run. In the DVD commentary, Payne says this choice was made deliberately, to suggest that McAllister is in a sort of prison—that all teachers are. One theme of the film, as discussed below, is the use of circles and triangles, which is not only connected to the theme of apples (and other fruit) but is used to suggest that while achievers like Flick move forward in life, teachers like McAllister suffer a fate of rote repetition and mediocrity. Teaching is a Sisyphean task that goes around in circles, as this voice-over by Flick reveals, juxtaposed with a short montage of McAllister reciting the same lessons and going over the same motions, including drawing triangles (and later circles) year after year:

“Now that I have more life experience, I feel sorry for Mr. McAllister. I mean, anyone who’s stuck in the same little room, wearing the same stupid clothes, saying the exact same things year after year for all of his life, while his students go on to good colleges and move to big cities and do great things and make loads of money – he’s gotta be at least a little jealous. It’s like my mom says, the weak are always trying to sabotage the strong.”

This quote serves two purposes. It reveals Flick’s true nature, characterized by conceit and a general mean-spiritedness, although her animus towards McAllister is somewhat understandable from her perspective. In addition to this, however, the voice-over quote and montage further advance the disparaging, overtly negative portrayal of teachers in American public education and Jim McAllister in particular. This is all the more remarkable because McAllister won Teacher of the Year three times during his twelve year tenure, and is shown for his dedication to and involvement with his students.

McAllister is further made an object of ridicule by the diminutive economy car he drives, a Ford Festiva, year unknown but probably late 80s or early 90s.4 In the commentary, Payne chides McAllister for his car, “the Ford Festiva, the car of choice of the impotent man,” alluding to difficulties McAllister has in impregnating his wife. The very manner in which he conjurs the idea of convincing Paul to run is also cringe-inducing; during a sleepless night, he wanders down to the basement to watch one of the pornographic VHS cassettes he keeps in a false bottom of a hope chest. The pornographic video shows a woman and a man in the doggy-style position, with the woman playing the role as a cheer-leader and the man a football player, with some (black) comedic effect as the man, sporting a widow’s peak, is probably in his early 30s. Finally, the way McAllister leches after Linda, the estranged wife of Dave Novotny, is pathetic, not just because it is in contravention to marital vows taken, but also because the woman is not very attractive. This is compounded in the ham-fisted, clumsy way he propositions her while driving back from a trip to the mall while driving past a cheap motel.

A greater consideration impugning McAllister as a protagonist is that he is usually, but not always, an unreliable narrator. In one voice-over narration, he says his animus towards Flick has nothing to do with the sexual impropriety that ruined his friend and former colleague. When she hands over signatures at the end of the school day, running toward his car before he drives off, his body language clearly signals resentment and exasperation for something. What is it if not lingering resentment over the fate of his friend? As explained below, her unsavory personal traits are likely the bulk of it, but his knowledge of what has been kept hush-hush is a quantifiable factor in the equation as well.

Elsewhere in the movie he professes love for his wife, Diane, saying their relationship is great, and yet they are shown eating quietly together, with a palpable sense of alienation and even lack of interest on both sides. By the end of the film, McAllister cheats on his wife with Linda, before Linda double crosses him after they agree to rendezvous at that cheap motel once school is over. During intercourse he is also shown first thinking about Linda. Then Flick herself suddenly comes into his head, indicating there is in fact some unresolved tension with the student that he is grappling with. Some have used this detail to suggest McAllister is not that much different than Novotny. With this single solitary instance excepted, he is never shown or suggested to have any lewd or sexual thought about Flick by way of glance or salacious comment. This contrasts with how he is shown to have sexual thoughts for Linda, by looking down at Linda’s cleavage while on a ladder, and before that looking at her ass in somewhat form-fitting “mom jeans,” to mention nothing of his “should we get a room” gaffe. The tension surrounding Flick’s stated desire for their “relationship to be harmonious and productive” after running to his car similarly stems from broad, general anxiety over the fate of his friend and what he observes of her personality in other contexts. This belies the assertion that he was leching after Flick, an accusation she herself makes after being—correctly—accused of tearing down the posters. Indeed, he sets forth a plan to convince Paul Metzler to run against her, and even throws the election in a forlorn bid to prevent her from winning the election. These actions are the very antithesis of grooming or leching.

That McAllister is an unreliable narrator, at least in some or even most instances, creates further ambiguity concerning his fate and the aftermath of the election scandal, as well as ambiguity in the struggle that ensued between him and Tracy Flick. This is compounded by his pathetic portrayal in the movie, certainly while as a teacher. The ending is somewhat more ambiguous. Some viewers suggest he is not much more than a tour guide at The Museum of Natural History; he even wears a badge reading “Museum Guide.” Point of fact, he describes himself as a “museum educator,” an actual position that, while not as lofty as curator, is not merely a tour guide or docent, either. He is shown to dress somewhat better, with a decent hair-cut, and his girlfriend Jillian is more attractive than either Diane or Linda, although, while modestly attractive, is no knock-out. While his narration about Diana does not match the alienation and estrangement we see at the dinner table scene and what unfolds at the end, he and Jillian are shown to like one another in body language and other tells.

It is also noteworthy that his unreliable narration cracks in the second to last scene when he sees Flick years later, impotently throwing a Pepsi cup at the limo she is riding with a Congressman from Nebraska.

I'll never know if she saw me. Probably not. But in that moment, all the bad memories, all the things I'd ever wanted to say to her, it all came flooding back. My first impulse was to run over there, pound on her window and demand that she admit she tore down those posters, and lied and cheated her way into winning that election. But instead, I just stood there. And I suddenly realized I wasn't angry at her anymore, I just felt sorry for her. I mean, when I think about my new life and all the exciting things I'm doing, and then I think about what her life must be like... Probably still getting up at 5 in the morning to pursue her pathetic little dreams. It just makes me sad. I mean, where is she really trying to get to anyway? And what is she doing in that limo? Who the fuck does she think she is?

The suggestion that he “wasn’t angry anymore” is belied by the last three sentences, and his outburst where he throws a soda cup at the limousine. While he has arguably rebuilt his life to some modicum of stability and livability offering something more than just abject misery, his divorce and his disgraced exile from the teaching profession are part of his past. This consideration reveals how very often an individual can never truly overcome his past, that however much one may say he is over the past, the past is never quite over for him or anyone.

How ever any viewer chooses to interpret the end and whether McAllister redeems himself in whole or in part, the unreliable narration remains a hallmark characteristic of Jim McAllister, but does this pertain to his animus towards Flick? Unlike these other instances where the viewer can see the discrepancy between McAllister’s narration and what the viewer discerns and sees with his own eyes and ears, the viewer observes Flick’s negative qualities, usually but not always while interacting with McAllister.

If one were to choose one word, and only one word, to characterize Flick’s personal qualities, both negative and positive, some would doubtlessly choose “ambitious” or “driven.” Consider however an even better word choice to characterize her, one that distinguishes her from other ambitious people. That word is duplicitous. Consider for example her disingenuous campaign speech before the school assembly, in which she submits that each and every student will be voting “for yourself” when voting for her. Her true, duplicitous manner is revealed when the viewer compares that speech for example with the disdain with which she regards many of her fellow students when questioning the authenticity of the signatures Tammy had gathered to qualify in the election just before the deadline. “These are a bunch of burnouts,” she protests.

Compare her glad-handing, fake smile schtick with the way she confronts Metzler for doing nothing other than daring to run against her in a student body election.

Her duplicity is further revealed in how she dresses down McAllister for (correctly) interrogating her about the posters she tore down. This is then soon juxtaposed with the goody-two-shoes, Patty Duke routine she pulls the morning after, when McAllister comes to school with a swollen eye from a bee sting after a sleepless night in a car parked outside the Novotny home after being ousted by his wife.

These two excerpts provide a perfect contrast between Flick with her mask off and Flick with her mask back on. Flick is defined above all by her abject duplicity.

Such duplicity is layered with a certain over-bearing manner tied to her self-serving ways, as revealed in key moments, including her admission that she “volunteered for every committee” in student government, “as long as [she] could lead it.” As she says this, she is shown to treat her fellow students in her characteristically overbearing manner, as the camera then shows McAllister observing, quietly, crossing his arms.

Her true nature is further revealed when comparing her musings about “talks” she had with Novotny and the way she nonchalantly photoshops his likeness out of yearbook photos, without so much as batting an eye. Less ambiguous given the immoral and criminal nature of that relationship, but the overall composite of behavior reveals her to be a phoney nonetheless. This is particularly so as she is shown doing this photo-shop work as she disparages her fellow students as “ungrateful” for the alleged sacrifices she makes working on the yearbook to “give them their stinking memories.” McAllister, despite all his faults, perceives these character traits better than anyone. Paul does not see it, despite her appalling behavior towards him, as he is far too good-natured to hold it against her even if he did. Other students do see these traits, but not in the crystal-clear manner that McAllister does.

McAllister knows of course Tracy Flick tore down Paul’s posters, and while he senses Tammy is lying, he cannot prove it, nor can he comprehend, at least not fully, that Tammy takes the blame in order to get purposefully expelled, so she can go to an all-girl Catholic school better suited to her lesbian proclivities. McAllister of course was preoccupied that day with the morning tryst he had with Linda, and the planned rendezvous they agreed to at the cheap motel “like [he] wanted. ”. This raises the question whether he would have taken Tammy’s unconvincing confession if he were focused on what he was doing and what was going on.

Scott (the New York Times reviewer) dismisses the destruction of a rival’s posters and lying about it as unimportant, but it was an unfair advantage nevertheless. She lied about it, letting Tammy take the fall, as this incident reveals her deceitful, self-serving, and even-mean spirited nature. One could even argue her dishonesty regarding this was of greater import than McAllister throwing the election, because most voted for neither candidate (ostensibly in favor of Tammy Metzler, who was disqualified by falsely confessing to get expelled) and because, on a fluke whim, Paul decided not to vote for himself but Tracy Flick. That idiotic decision changes the tally from 256-255 in favor of Paul, to 256-255 in favor of Flick.

Flick’s true character is further defined by another quality, one that defies any single word, but “disingenuous” and “hollow” combined together come close. In her first voice-over montage, she mentions all the extra-curricular activities she does: starring in Fiddler on the Roof, running for student council and later president, yearbook, and acting as correspondent on the student run “tv station.” She does none of these things out of an intrinsic interest in these pursuits as ends unto themselves. She did not take a role in Fiddler on the Roof out of any discernible or stated interest in drama and acting, she took a role in that play, as she does everything, to put on her transcript for college admissions. Nor does her work on the yearbook seem to stem from an interest in publishing, photo-journalism, or writing. Her drive for academic excellence does not seem to derive from any intellectual interest or curiosity; her academic pursuits are merely for the sake of credentialism, and credentialism alone. Indeed, the brief glances we are provided of her bedroom do not show an adolescent’s interest in favorite musical artists or young adult fiction or any personality trait or interest that makes a person human or relatable. It is all centered around her awards and accolades, as well as kitschy posters with motivational slogans. Astute viewers also get a brief glimpse of her desk, highly organized with a bulletin board with post-it notes arranged like one might see in a police task force command center or the like, but with a strangely feminine tinge. There are no band posters, no images of heartthrobs for teenage girls, no posters of Wuthering Heights.

These and other instances observed by the viewer reveal Flick to be disingenuous, self-serving, duplicitous, as well as hollow—traits that McAllister and McAllister alone sees and understands in ways other characters do not. This key consideration explains why many viewers side with “Team McAllister,” or rather against “Team Flick,” his many short-comings notwithstanding.

These and other considerations reveal how revisionist retrospectives, such as those offered by Scott, miss the mark in suggesting that Flick is the heroine. McAllister has many faults, which include both personal failings and a marked dissonance between his narration and what the viewers see and hear for themselves on various matters—except Tracy Flick’s duplicitous and self-serving manner. Despite these failings and flaws, McAllister was right about Flick. His methods were flawed, at least at the very end, and he was ultimately proven incapable of ameliorating these flaws, but he was right nonetheless, even though the world in this film does not recognize this hidden truth revealed to the viewer.

Ethics Versus Morals

A prominent theme in this film and a theme directly related to the “Flick versus McAllister” debate is the important distinction between ethics and morals, two terms that are often and erroneously used interchangeably in common parlance as well as in the film’s very dialogue. This key distinction is presented to the viewer in the beginning of the film, when McAllister’s narration reveals the illicit sexual affair Novotny is having with Flick. After showing how this all unfolded, the narration soon goes to a “flashback” where Novotny informs his friend and colleague of a sexual encounter in the Novotny home. After objecting “you did it in your house, your own house,” the following dialogue ensues:

JM: Dave, I'm just saying this as your friend, what you're doing is really, really wrong and you've gotta stop. The line you've crossed is... it's immoral, and it's illegal.

DN: Jim, come on, I don't need a lecture on ethics.

JM: I'm not talking about ethics, I'm talking about morals.

DN: What's the difference?

The film never explicitly tells the viewer the difference between the two, but astute viewers will discern this distinction independently, on their own. The difference between morals and ethics is fundamental, and one that plays into the plot of this film. McAllister’s spur of the moment decision to “throw” the election was, without question, unequivocally and absolutely unethical as a teacher or as any election official, whether for student body or elections that (more or less) matter. Whether it was moral or immoral may be a subject of debate, however, depending on to what extent a viewer determines McAllister’s animus for Flick to stem from legitimate or illegitimate reasons, and to what extent the ends justify the means; as explained above, her various negative qualities seem obvious and indisputable. To the extent he knew but could not prove Flick destroyed Paul Metzler’s campaign posters, or discerned at the moment that most votes were “disregards,” rendering the whole matter a farce, some might consider his decision to be righteous, and that the only wrong thing he did was the careless manner in which he discarded the two ballots to change the tally from 256-255 for Flick to 255-254 for Metzler: that the only wrong thing he did was get caught. McAllister was undone by the school janitor who harbored his own animus towards the teacher for no other reason than, when cleaning out a disgusting refrigerator in the faculty break room, he tossed spoiled Chinese take-out, aiming for a trash can just behind him, but missed.

One important qualifier is that McAllister did not set out from the beginning to throw the election. He simply encouraged a student to run for student body president, which is perfectly within his right to do, a consideration Scott and other Flick apologists overlook. McAllister specifically notes he was about to announce that he came to the same tally, until he saw Flick spying on them, jumping up and down. With this consideration in mind, the film offers an interesting juxtaposition between ethical breaches of conduct by teacher and student: McAllister discarding two ballots to change the election outcome, Flick tearing down Paul’s posters in a fit of rage and frustration after inadvertently ripping her best, most elaborate poster: wrong-doing that also seeks to change the outcome of the election. Does such breach of student ethics rise to the level of cheating on an exam? Many private schools and more particularly colleges and universities have honor codes rendering such dishonesty grounds for expulsion. Does it matter that each was a spur of the moment decision, as a mitigating circumstance? The distinction between adult student and minor student (a 17 year-old junior in high school) certainly matters. Regardless of these and other nuances, McAllister was caught, Flick was not. In very important ways, that is all that really matters, bolstering the blithe assertion that McAllister’s real wrong-doing was being sloppy and getting caught.

The ethical versus moral dynamic is also relevant to how he handled Novotny’s wrongdoing. Particularly as society has regarded teacher sex scandals and matters like the #metoo movement with greater sensitivity, some view McAllister’s failure to report Novotny as another consideration that reveals him to be unsavory, deplorable even. Since the time this film was made and the setting the narrative takes place in, teachers and other similarly situated professionals have been deemed through various statutory laws to have an affirmative duty to report discovery of any such incident. This duty rises out of the custodial duty of care a teacher has for his students and students generally, and the failure to report such knowledge, even in the absence of any other wrong-doing, can invoke a variety of negative sanctions, including termination of employment, revocation of license, and even possibly criminal sanctions. This standard did not exist in the 90s in relation to improper sexual relations between a teacher and a student Flick’s age, at least not as far as this author can discern.5 Such strong rebuke of McAllister too readily dismisses or disregards his unequivocal opposition to Novotny’s sexual misconduct, stating full stop “I don’t want to hear that, don’t tell me that” and, later, that it is “morally wrong, and illegal.” Still, his decision not to report does raise serious ethical and moral concerns, although the moral choice involved is in tension with duties of loyalty to one’s “best friend” and what he felt was the best strategy to stop this from continuing further.

The difference between morals and ethics is an important, fundamental distinction that the film imparts to its viewers through narrative, informing how one might judge McAllister on the moral versus ethical divide of his effort to “throw the election” as well as what in legal parlance is known as “omission of action” by not reporting Novotny. This prism lends itself to many moral and ethical dilemmas in both real-life and fiction. Consider for example that the protagonist in Cape Fear, Samuel Bowden, breached legal ethics by not offering the most zealous defense to his client, Max Cady, but was at the same time a moral decision because he knew Cady was guilty. Similarly, the decision to offer the most zealous defense of such a client may be in compliance with legal ethics, but may be considered immoral by many.

Other Themes and Motifs

Payne is particularly admirable for his use of symbolism and recurring themes. One of the most important themes, discussed above, is the distinction between morals and ethics. Another prominent theme is the use of fruit, particularly apples, as seen throughout various stages of the narrative. During his effort to convince Paul to run against Tracy Flick for student body president, McAllister talks about democracy as a choice. He asks Paul what his favorite fruit is, the popular student oscillates, first stating pears, before changing his mind to apples. He even states a few seconds later that he “also like[s] bananas”, after McAllister draws a choice between “apples and oranges” to demonstrate how democracy offers the people a choice, which is in fact shown to be a choice between two identical circles on the chalkboard. This in itself suggests cynicism about democracy. After school has ended, Paul stops briefly at the fruit basket on his parent’s kitchen table filled with apples, oranges, and bananas, and takes a banana before going to greet his disaffected sister, an important moment which explains her motivation in running against her brother. Taking the banana suggests he is not the orange to Flick as apple, foreshadowing his decision to vote for her and his eventual loss. It is also noteworthy that when McAllister is looking for Linda after she fails to show up at the rendezvous, he walks by an apple tree before being stung in the eye by a bee. The allusion to the story of Adam and Eve and the forbidden fruit is obvious. The bee sting further foreshadows McAllister’s downfall, both with Linda betraying him, which leads to divorce, and the election scandal destroying his career as a teacher. By associating the bee sting with the apple, this foreshadowing, by way of the bee sting and subsequent swelling of his eye, is further linked to his decision to persuade Paul to enter student body president election, in which Flick had been running unopposed. Flick as the only available choice for class president was of course compared to apples when McAllister convinces Paul to run. Earlier, after his clumsy attempt to proposition Linda to go to a cheap motel, he is shown grabbing an apple from his refrigerator, a foreshadowing of the film’s ending that suggests Flick’s triumph and his failure is written in the stars. This is especially palpable as the open refrigerator reveals not Pepsi, but a pack of Coca-Cola, suggesting his effort to foil Flick, who compares herself to Coca-Cola, was not attended with sufficient care and focus. His ultimate failure and her success are even stated to be a matter of fate, as Flick states at the beginning:

You can't interfere with destiny, that's why it's destiny. And if you try to interfere, the same thing's just going to happen anyway, and you'll just suffer.

The war between Coca-Cola and Pepsi is another theme, as Flick tells McAllister after submitting her signatures in the parking lot how Coca-Cola spends more on advertising than other soda concerns, “which is why they stay number one.” This links Flick to Coca-Cola thematically and in the mind of the viewer. When McAllister throws away her signatures (after certifying them or noting them as the overseer of student elections, one supposes), he also throws away an empty bottle of Pepsi. McAllister happens to be drinking a Pepsi while watching the porno that inspires the idea of getting Paul to run against Flick in his head. The theme runs full circle during the final scene where McAllister sees Flick years later in Washington, as she enters a limousine with, the viewer learns, a Republican Congressman, for whom she is ostensibly working as an aide. Holding a paper cup with Pepsi branding and lettering, he throws the soda at the back of the car, splashing the car with ice and soda, before the driver stops and accosts him and he scampers off: a microcosm of how impotent and forlorn his efforts to stop Flick were from the very beginning. Another theme alluded to earlier, which Payne himself has discussed, is the recurrent motif of McAllister drawing circles and triangles, suggesting that, as an educator in American public education, a profession Payne mocks and chastises in the film, he is stuck in a groove, going in circles, which is emphasized during the voice-over narrative by Flick discussed earlier. McAllister is also associated with trash and garbage throughout the film, and important theme but one that will be merely mentioned in passing.

Final Thoughts

The film is endowed with many other charms and attributes besides those explored heretofore. With Matthew Broderick as the lone exception, the cast consists of mostly lesser known or even unknown actors, or at least were not well known at the time. Reese Witherspoon had only starred in Cruel Intentions and Pleasantville before being cast in this break-out role. Election was Chris Klein’s debut into Hollywood. Most viewers would not recognize Colleen Camp as Flick’s doting mother. Notably, Payne cast mostly high-schooled aged students to play as extras and small roles as other students, lending the film an authenticity not seen in better-known films set in high school, such as Breakfast Club, Fast Times at Ridgemont High, or even Mean Girls, all of which feature cast members who are too old to portray high school age students convincingly.6 The film also has a wonderful and unique soundtrack so very distinctive to Election, rendering the film instantly recognizable sight unseen, when heard playing in a different room for example.

Another excellent trait of the film is how it depicts the ulterior motives of some of the players involved, and how others invariably fail to discern such motives. This particularly pertains to the motivations of Lisa Flanagan and Tammy Metzler. Lisa makes sexual advances on Paul in order to make Tammy jealous (they had exchanged kisses and were, as Lisa, says “experimenting,” although Tammy was beyond romantically infatuated, writing notes professing an intention to throw herself in one of her dad’s cement trucks if Lisa ever died so that she, Tammy, would be thrown in her tomb). Tammy’s principal motivation for running is in direct response to what she correctly perceives as Lisa’s efforts to hurt her. Lisa alone perceives this, and divulges this when she says ‘she is doing this to get at me,” before correcting herself, stating “I mean to get back at you” when they object to Tammy’s candidacy to McAllister. McAllister heard this, but never gave it the thought and consideration it deserved. To the extent he perceives these intentions at all, particularly with Tammy, he does so only dimly. Indeed, had he been able to fully discern Tammy’s motivations for running against her brother, he might have been able to “crack the code” and demonstrate, beyond just mere intuition or suspicion, that Tammy lied about tearing down the posters.

Perhaps most importantly, the film offers the viewer all of these observations and insights in the most amusing and entertaining fashion. Despite some of the heavy-subject matter, including a teacher’s sexual impropriety with a 16-17 year-old junior in high school, infidelity and divorce, exposing and mocking American public education and received norms about meritocracy as a farce, portraying most teachers to be studies in the mediocre and the pitiful, the film is really funny, in an understated way, with an almost dry sense of humor. The manner in which Tammy follows Lisa and Paul around, spying on their intimate moments from putting up campaign posters together to sexual intercourse like a bumbling cartoon detective is hilarious. It is also somewhat amusing seeing her ride down to the campus of Immaculate Heart, looking at all those catholic school girls, just as it is amusing how she purposefully designed and executed her expulsion to be placed there, and all of the adults were too stupid or too distracted to see through her ruse. The attire and mannerisms of the esteemed educators, made to be an object of ridicule, are also amusing to those who suffered through the nonsense that is American public education. McAllister’s downfall the day of the election is grim, but hearing him mock Tracy and her constant demands and need for attention before declaring “fuck them” while cleaning up in the shower is both funny and relatable. His exasperation about the formalities demanded by Larry Fouch, the student who underwent the first count, exclaiming “We’re not electing the fucking pope” is another funny jab, one of many.

Election may not be on every list of greatest films (100, 50, or whatever the case may be), and may not yet have been selected by Congress for preservation due to cultural significance, but it certainly deserves such distinctions and much more. The film makes crucial observations about American education and society at large, provides key psychological insight into various personality types, and does all of this in a thoroughly entertaining and amusing way. Election receives and deserves the very highest possible recommendation. Five stars, 10 out of 10.

PLEASE NOTE: This essay appears in the section Books and Film. There readers will find other interesting and noteworthy reviews and essays, including reviews and commentary of Matt Walsh’s Am I a Racist, the Netflix abomination Will and Harper and Andrew, as well as a review of a recent film called Substance. The last review may be of particular interest to readers of this publication, as the film is bound up in issues concerning feminism, feminist tendency to blame men (and only men) for what they perceive as unrealistic beauty standards and other important topics. New subscribers and readers unfamiliar with this section are encouraged to peruse the essays there. The review of Big Fan is also recommended, as is the comparative analysis and review of Can’t Buy Me Love and I am Charlotte Simmons. Finally, readers looking for film recommendations are encouraged to peruse this list.

Those who are able to are urged to consider a paid or even founding membership to support and further this endeavor.

Finally, follow Richard Parker on twitter at (@)astheravencalls. Delete the parentheses, as these were inserted to avoid interference with substack’s own handle system.

NOTES

One choice, probably the one that contends for the choice of just one single, solitary favorite that is mentioned less and less but is still one of the greatest films of all time is Amadeus. Some of the films on this list are all time favorites, while others are just good films that others should see if they have not already.

Yes, dear readers, Joyaux used the term “media literacy,” and did so unironically.

Quite bafflingly, this hack seems to think no viewer has any reason to feel aversion for the future in-laws in About Schmidt, just as he similarly juxtaposes Tracy Flick with the protagonist in Rushmore, without accounting or acknowledging many of Tracy Flick’s very negative characteristics and even pathologies. One of course cannot engage in a “reading” of a film, unless perhaps it is in a foreign language one does not understand; “interpretation,” “analysis,” and the like are the proper terms.

If McAllister saw Flick one last time in a near contemporaneous timeframe as the film’s release (1999), it can be surmised that Flick’s junior happened around the 92-93 or 93-94 school year, graduating high school in 1994 or 95, college around 98 or 99 and worked as an aid thereafter. McAllister’s winter clothes indicate he did not see her in the summer, precluding her working as a summer aide.

An inquiry reveals that § 28 211 of the Nebraska code was in effect, revised in 2005. That law imposes a “mandatory reporting” requirement for school employees and others upon discovery or belief that “child abuse” or “nelgect” has occurred. The age of consent in Nebraska was and still is 16 in Nebraska, and—most crucially—the statutory prohibition (§ 28-316.01) against the sort of improper teacher student relations at issue here was not enacted until 2009.

Judd Nelson was 24 when Breakfast Club was filmed. Robert Romanus was 25 when Fast Times at Ridgemont High was filmed. Rachel McAdams was 24 turning 25 when Mean Girls was filmed. Both Eric Stolz and Lea Thompson were 25 in Some Kind of Wonderful.