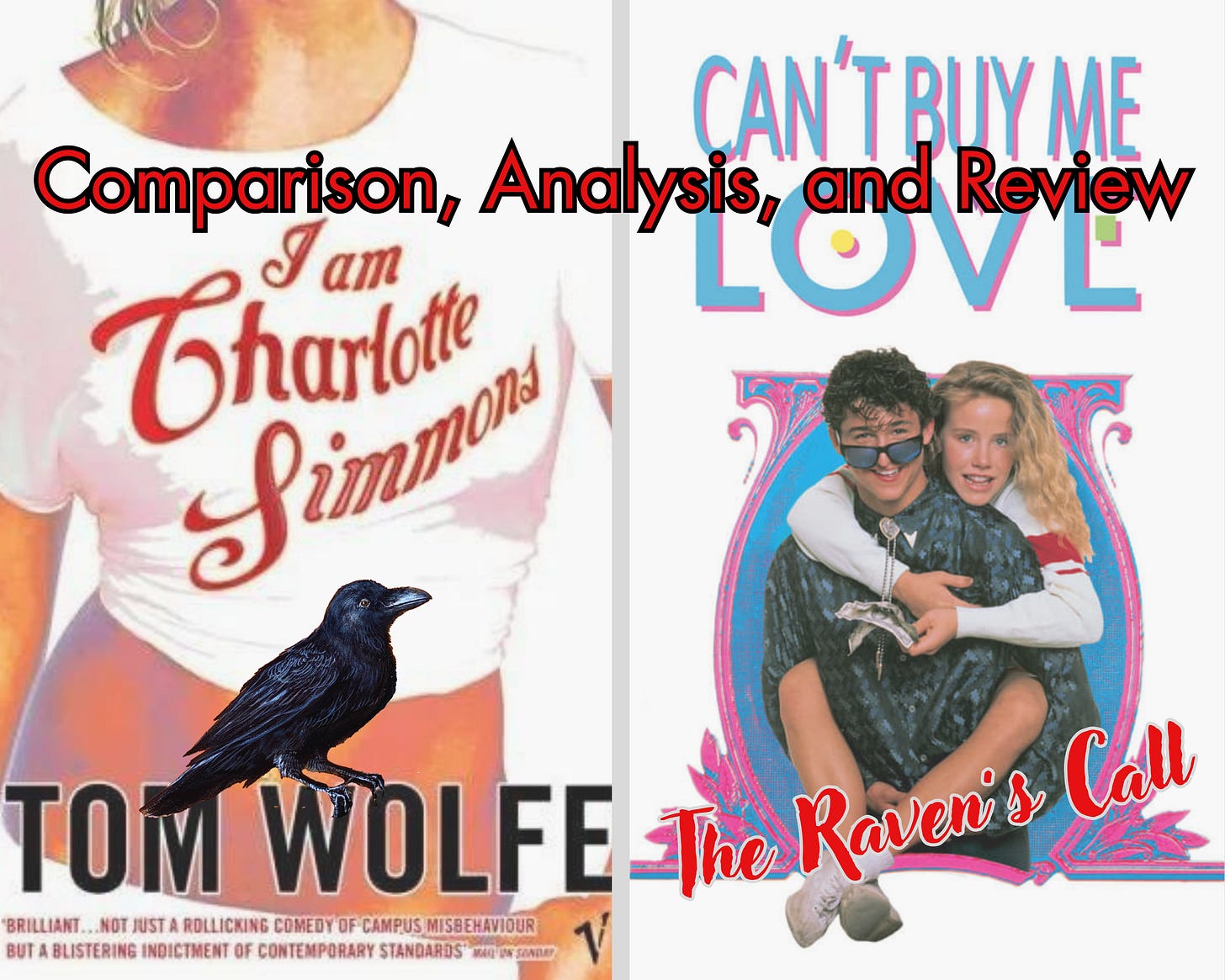

Smitten with Charlotte and Cindy

Exploring Themes of Social Proof, Hypergamy, and Groupthink in Can’t Buy Me Love and I am Charlotte Simmons

AUTHOR’S NOTE: this essay contains significant SPOILERS, revealing the end result of each narrative.

Two works of fiction have been very influential in this author’s thinking on a wide range of subjects: a film, “Can’t Buy Me Love” (1987) and a book, Tom Wolfe’s I am Charlotte Simmons, published in 2004. The first concerns adolescent, suburban high-school life in the 1980s and the other concerns young college life at the turn of the millennium. Both works center around a very attractive blonde woman with multiple suitors. Set in Tucson, Arizona, “Can’t Buy Me Love” stars the most alluring but tragic actress, Amanda Peterson, who plays the role of Cindy Mancini. The counterpart in Wolfe’s novel is, as one might guess, Charlotte Simmons. Not at all a popular rich kid in an American suburban environment, Charlotte was raised in poor Appalachia. Whereas Cindy dates a lot of different young men (it is suggested she dates but does not sleep with most except her former high school boyfriend who graduated the year before and is now at college), Charlotte, although possessing natural beauty, is, at least to start, sexually chaste and very religious. It is suggested Cindy does well enough in school, whereas Charlotte was a local academic prodigy, earning straight A’s to earn a full scholarship at “Dupont University,” a fictional school which is clearly an amalgamation of what Wolfe observed while at Chapel Hill and more particularly Duke University while doing research for his novel.

Both works involve an unlikely suitor who pursues Charlotte and Cindy. In Can’t Buy Me Love, the narrative focuses on the protagonist of that story, Ronald Miller, played by a young Patrick Dempsey. Conversely, Charlotte Simmons is the protagonist (of sorts) in Wolfe’s novel, who is pursued by three different college men, all of whom come from very different backgrounds: Hoyt Thorpe, an obnoxious fraternity man confirms most if not all most stereotypes about the Greek system, JoJo Johanssen, the sole white player on the school’s basketball team, and Adam Gellin, a half-Jewish kid who, unlike the other suitors, actually applies himself in school and earns good grades. Unlike the other two suitors, Adam is not well-to-do, and must work part time while attending classes at “Dupont.” Adam also works on the student newspaper, while belonging to a small clique of nerdish students who call themselves the “millennial mutants,” whose airs and mannerisms Wolfe mocks in masterful fashion. Neither Hoyt nor JoJo are good students. Hoyt’s grades are so bad he derisively refers to his grades as a crime scene. JoJo on the other hand discerns that the courses he takes are an academic fraud, courses set up by the administration and athletics department to issue fraudulent grades to “student” athletes, so as to provide them passing grades necessary to avoid academic probation and remain eligible under NCAA rules. At some point during the narrative, JoJo refuses to take these courses, against the directive of his basketball coach, and takes normal courses for other students because he is tired of being seen as a “dumb jock.” Another critical fact for a parallel plot discussed later is that Adam is also compelled to work as a “tutor” for JoJo, but in fact is effectively writing his papers for the student athlete, as part of the academic fraud described above.

Whereas Charlotte Simmons is the central character in that narrative, the central figure in Can’t Buy Me Love is Ronald Miller, who, despite his low social status among his peers, longs after the hottest girl in his high school, Cindy. Cindy is rich, a cheerleader, and corrals with the other rich, popular kids in school. Ronald is not popular, but a nerd who applies himself in school, and takes a pronounced interest in astronomy among other subjects. This film of course was made before the word “geek,” an insult in the 80s, was “taken” by those for whom the term was applied; i.e. the film exists in a time and youth culture when the word “geek” did not have the “hip factor” it has had since about the turn of the millennium. It is in that particularly onerous subtext that Ronald Miller, a smart nerdy kid, desires the incredibly beautiful and utterly unobtainable Cindy. He pines after her in the denigration of mowing the lawn for Cindy’s rich, divorced mother, something Cindy’s friends mock him for.

Seconds before disaster, Cindy is admired by all her friends, wearing her mother’s expensive suede garment.

Harboring the strong desire for the unobtainable blonde as he does, he learns of a predicament Cindy finds herself in. While her mother is away for the weekend, Cindy holds a party for all the popular kids at school, a party typical of both 80s teen movies and real life, with lots of alcohol and more than a little debauchery at hand. Cindy had asked her mother, from whom she inherited much of her beauty, if she could wear her mother’s revealing suede, crème-colored outfit. Her mother tells her no, but Cindy wears it anyway during the party. Predictably enough, one of the football players spills red wine over the garment. Cindy goes to the high-end boutique where her mother bought the garment, desperately inquiring to see if dry-cleaning is an option, but the stain is permanent. With a replacement costing $1000,00 (in 1987 dollars, which is nearly 3,000 today), she is unable to replace her mother’s garment. Meanwhile, Ronnie is at the mall intending to buy a telescope he had saved up for, also priced at $1,000. After observing her pleading with the shop-owner to let her work after school in exchange for a replacement, Ronald approaches her with this proposition: he will give her the $1,000.00 dollars so that she can buy a replacement garment, leaving her mother none the wiser and avoiding what Cindy anticipates to be a severe and drastic punishment. In exchange for the thousand dollars, she will agree to go out with him for a month.

With a fistful of dollars, Ronald makes a proposition. On the right, Cindy and Ronald have lunch together for the first day of their arrangement.

Cindy reluctantly agrees, but not without little insults here and there. During that time, Cindy helps Ronald style himself better, out of kindness but also out of self-interest, so as to diminish or minimize the embarrassment or disapproval she could face for going out with him. The month comes and goes, and despite her strong hesitation in the beginning, Cindy comes to like Ronald, even if in a “friend-zone” sort of way. Ronald however notices that, because their peers perceive Cindy to be dating Ronald in earnest, other popular girls, who regarded him with disdain and scorn before, suddenly take a strong interest in him.

Sensing an opportunity, Ronald double-crosses Cindy, breaking up with her before she breaks up with him per their agreement, and does so in a way that draws considerable attention from the entire high school. This increases the sexual interest from Cindy’s friends even more. As a result, Ronald is able to have sex with several of Cindy’s hot cheerleader friends—hot but not quite as hot as Cindy, as they are curiously all brunette. Because the popular hot girls do not know about the arrangement, they perceive Cindy’s feigned interest as proof of Ronald’s desirability.

This is known as social proof, a powerful psychological phenomenon where people look to others decisions or beliefs and conform their decisions and beliefs based on what others do, say, or believe. People often look for social proof in ambiguous or novel situations as a sort of short-cut in place of pronged deliberation or contemplation. The social proof by way of Cindy’s perceived favor for Ronald also convinces two of the popular football players to befriend Ronald in instantaneous fashion, despite being utterly contemptuous of him up until he was perceived to be dating Cindy. That added social proof in turn convinces much of the rest of the school to look upon Ronald favorably, as he is now, in a few short weeks, one of the popular kids.

In this way, Can’t Buy Me Love is very much a case study of Friedrich Nietzsche’s concept of the herd mentality. There is even a scene where Ronald, to prepare for a high school dance, decides to watch American Bandstand to learn how to dance in front of his new, popular “friends.” A brother, unbeknownst to Ronald, turns the channel to PBS, showcasing an African ritual dance, which Ronald incredulously thinks is American Bandstand. At the dance, he mimics the African ritual dance, looking objectively ridiculous. But, because he is the new popular kid who went out with Cindy Mancini before dumping her in rather spectacular fashion, they allow follow along, like mindless sheep.

Cindy seethes in resentment as November and then December go by, until finally, during a New Year’s Eve Party in which her (former?) boyfriend now at college mocks her for going out with Ronald. In the wake of that latest indignity, she outs Roanld in front of everybody, telling the entire party that their dating history was a fraud, that he paid her $1,000 to date her. This utterly humiliates him and he becomes a social pariah who is accepted by neither the popular kids nor the nerdy kids who used to be his friends. Now that the “social proof” Ronald had by having “dated” Cindy is revealed to be a fraud, the hot girls who were throwing their bodies at him are once again repulsed by him. By the end of the movie Ronald and Cindy (somehow) reconcile and, as she becomes exasperated with the sorts that she had been dating for treating her the way they do, Cindy takes a bona fide romantic interest in Ronald and the film closes with the two driving off in his lawn mower, with the extremely desirable Amanda Peterson sitting in his lap with her arms around him, as the Beatles song “Can’t Buy Me Love” is heard as the credits roll.

The plot of I am Charlotte Simmons has similar themes concerning social proof and the mechanics of female sexual attraction. Charlotte goes to “Dupont” (really Duke by another name, with bits of Chapel Hill thrown in). She is hopelessly naïve and utterly unprepared for what awaits her. In reflecting on the novel, one suspects her character took Dead Poet’s Society far too seriously. She goes to school expecting a “life of the mind,” a phrase oft repeated by the narrator and in dialogue, with more than a little derision and sardonic wit; instead she finds unbridled, raw debauchery, particularly in way of her dorm mate, Beverly, a rich, suburban white girl whose “body count” goes up—and up—in very short order. At various points, Charlotte is “sexiled” from her dorm room as Beverly is fucking yet another college guy. Beverly is particularly fond of members—in the plural—of the Dupont Men’s Lacrosse team. Plunged in this debauched environment, Charlotte soon discovers that Dupont is not at all like something from Dead Poet’s Society. The emphasis rather is on the basketball team, drinking, and fucking.

While immersed in such abject profligacy, she draws interest from the three suitors mentioned above, Hoyt, JoJo, and Adam. Even though she is an outcast in many ways because of her disadvantaged Appalachian background and her chaste Christian musings, she is physically stunning. Initially, her morality renders her wary of Hoyt, whose promiscuity with other women was well known. She agrees to go on a date with him, where he invites her to his frat house, but it’s hands-off. In fairly short order, however, Charlotte, despite her moralistic sensibilities, is greatly influenced by her other female peers who tell her that Hoyt is “hot” and encourage her to continue to date him in no uncertain terms. The cat and mouse game between Hoyt and Charlotte continues for some time, until she agrees to go with him to a Greek formal, staying overnight at the hotel at which the venue is held. During the course of the evening Charlotte has too much to drink. Then, after Hoyt takes her back to their room, she is effectively date-raped; she tells him no after intense fondling and petting and he penetrates her regardless. After having claimed her as yet another sexual conquest, Hoyt quickly loses interest and immediately dumps her the next morning, even making derisive remarks about “hillbilly beaver.” Two sorority sisters (one is reluctant to call them peers of Charlotte in any meaningful sense of the word) mock and insult her mercilessly as well.

As a result, Charlotte suffers a crippling mental breakdown. It is then that Adam comes to her rescue, even taking her into his room, nursing her back to health. During this portion of the story, the omniscient narrator informs the narrator how Charlotte gazes at Adam’s face, and discerns he is, from a facial aspect, rather handsome. In ways reminiscent of Cindy’s makeover efforts with Ronald, the omniscient narrator recounts how Charlotte thought of ways to style him up to make him more desirable. The narrator also reveals that Charlotte begins to develop what could become an attraction for Adam reciprocal to his, until she discerns her female peers do not approve of Adam. And that short circuits everything. Adam’s goodwill to Charlotte ultimately counts for nothing, his handsome facial features count for nothing, nor does the fact that, of the three potential suitors, Adam is the only one who exhibits the sort of academic or intellectual prowess Charlotte claims to value. Actions, of course, always speak much louder than words.

By the end of the novel, Charlotte winds up with JoJo, a character who more or less splits the difference between what is represented by Hoyt and Adam. JoJo is not a good student, but unlike Hoyt, seems sensible and caring and wants to do better in school, as he resents being seen as a “dumb jock.” Earlier, Charlotte serves as a catalyst for his decision not to take fraudulent classes for student athletes, as he develops an interest in philosophy from his interactions with her before they start dating. Asides from his athletic prowess and build, the other key distinction between JoJo and Adam is social proof—JoJo, being a star basketball player, and the only white player on the basketball team—is successful with women, and the narrative even depicts him having a one-night stand with a groupie before he and Charlotte begin dating. After the sexual congress, he reflects on what has happened and what happens generally, and asks the strumpet why she does what she does. “Because you’re a star” is her reply. It is this success with other women, and most particularly the approval by her female peers of JoJo that is the determining factor as to why Charlotte Simmons chooses JoJo over Adam. The novel ends with her receiving a B, B-, C- and D during that first semester at Dupont, a disastrous result caused mostly by the nervous breakdown she suffered from the date rape and subsequent trauma. Placed on academic probation, the narrator reveals that she is confident she can improve going forward as she receives some notoriety for being the girlfriend of JoJo Johanssen. However, she is no longer concerned with living “the life of the mind,” but decides what is important is to be regarded as special, regardless of the reasons why.

The plot of how Charlotte Simmons manages and ultimately changes in the debauchery she finds herself in is intertwined with a parallel plot, in which Hoyt and some friends stumble on a Republican Governor of California and potential Presidential candidate receiving oral sex from a co-ed. The politician’s bodyguard interjects, but Hoyt beats up the bodyguard and runs off. This makes him even more popular on campus, particularly with the women. Despite his poor grades, it also leads to a job offer at Wall Street firm Pierce and Pierce (the same fictional firm depicted in Bonfire of the Vanities). This offer is nothing less than a bribe, as it is contingent on Hoyt’s silence. Adam, working on the student newspaper, investigates the matter and eventually breaks the story, something that bodes well for his future as he wins national acclaim for bringing down a Republican governor and potential Presidential candidate. Prior to that, a Jewish professor who resented the academic fraud perpetrated by the school to protect the eligibility of its student athletes determined that Adam was in effect doing the homework for JoJo in particular. This professor was set to file formal a formal complaint against Adam, which would have ruined his academic career, but, once Adam breaks the story, decides to keep it hush-hush due his hyper partisan politics and his interest in bringing down a Republican politician. The narrative includes a “mask-off” moment when the professor confides nepotistic favoritism for Adam given their shared Jewish heritage, although Adam is only half-Jewish.

A central theme of both Can’t Buy Me Love and I am Charlotte Simmons is the critical role social proof plays in female sexual attraction. The perception of such social proof among his female counterparts is what makes and later breaks Ronald Miller. Despite all Charlotte’s this-and-that talk about being a Christian and how she wants a “life of the mind,” she rejected, in rather short order, the one suitor who best exemplified those qualities, and did so only because her female peers disapproved. The omniscient narrator expressly imparts to the reader she thought he was handsome, and had enjoyed her time with him. Sensing only that her female peers disapproved was enough to thwart everything. In contrast, social proof as determinative of female attraction is undercut in Cindy’s change of heart in Can’t Buy Me Love, taking a romantic interest in “Ronnie” at the end. It is up to each individual viewer to determine how realistic such an outcome would be in real life. Even allowing for what could only be regarded as truly extraordinary outliers, the principle remains valid.

In the male mind, Natalie from Facts of Life is not rendered suddenly desirable because she has a relationship with a high status or highly attractive male.

And it makes sense intuitively. Imagine a friend who is a close approximation of Christian Bale or another male sex symbol, or even being friends with Christian Bale personally, or Clay Matthews III or whomever. Imagine further such a friend, however unlikely (this IS a hypothetical!), developed a sexual or romantic interest in a woman who was a dead-ringer for Natalie from Facts of Life, only for that relationship to end for whatever reason. Would “Natalie” suddenly become more attractive to the male friends of the Christian Bale look alike? No, of course, not. Conversely, a proverbial nine or ten goes out or has sex with a less attractive or flat-out unattractive male, and other desirable women will take an interest, most especially during that time and usually after. Women, even women who give lip service to things like chastity, or virtue, or “living a life of the mind” are attracted to male promiscuity. That of course has real implications, particularly for readers in young adulthood or even high school. It does not pay, it would seem, for men to be chaste or virtuous. Rather than adhere to proper morals, it might behoove a young man not to reject promiscuity, but embrace it. This is because if any woman in his life who knows other women are sleeping with him or want to sleep with him, that will not, in most instances, hamper his chances, but improve them. This principle applies most especially to any living incarnation of Freyja, the love goddess, as exemplified in the blondes in these works of fiction.

In response to those who might object that these are works of fiction, this key, fundamental dynamic of female sexual attraction is confirmed in any number of non-fiction works. F. Roger Devlin’s excellent treatise Sexual Utopia in Power explains not only how hypergamy predominates female sexual attraction, but that social proof is a key component of female hypergamy. There is also this New York Times article from some time ago, “The New Math on Campus,” exploring how young college women are experiencing difficulties in sex and dating, and are experiencing such difficulties despite women now outnumbering men on American college campuses with numbers as high as a 60 to 40 ratio. Quite fittingly, the article focuses on undergraduate life at Chapel Hill, one of the schools that the fictional “Dupont University” is a composite of. The article is a practically an applied study in misogyny, showcasing deplorable behavior by college women in a number of ways. Not having any respect for themselves, one wonders why anyone should have respect for them. They complain that there are no men available, as evidenced in this excerpt: “The experience has grown tiresome: they slip on tight-fitting tops, hair sculpted, makeup just so, all for the benefit of one another, Ms. Andrew said, ‘because there are no guys.’”

The cover image from the New York Times article “The New Math on Campus.” Both sides of the equation do not seem to equal zero, unless one factors in the ultimate wild card, social proof.

In actuality, and precisely as Devlin contends in his seminal tract, all the women are vying for 20 percent of the men. Note this statement from “Jayne Dallas, a senior studying advertising…,grumbl[ing] that the population of male undergraduates was even smaller when you looked at it as a dating pool.” Her direct quote could just as easily have been taken directly from Sexual Utopia in Power: “Out of that 40 percent, there are maybe 20 percent that we would consider, and out of those 20, 10 have girlfriends, so all the girls are fighting over that other 10 percent. . ..”1 Are the other 80 percent of college men, all between 18 and 23, all unattractive, or are these contemptible women succumbing to the herd mentality that ultimately defined Charlotte? The sheer numbers dictate that they are refusing handsome, otherwise perfectly acceptable young men like Adam only because those young men are not perceived to be desired by other women. The article further demonstrates how hypergamy and social proof define female sexual desire and morality or lack of morality, as revealed in this account by “Rachel Sasser, a senior history major” who confided to the reporter that “before she and her boyfriend started dating, he had ‘hooked up with a least five of my friends in my sorority — that I know of.’” Women like this do not see this as a red flag, they are attracted to it. The fact her boyfriend fucked five of her sorority friends does not indicate to her or those of her ilk in the slightest that he is prone to infidelity or promiscuity, it is confirmation of his desirability. Her boyfriend was good enough for five of her friends, so he is good enough for her is the specious reasoning that seems to govern the menstrual mind.

I am Charlotte Simmons also makes a very dramatic statement about the power of the cultural milieu that surrounds us all. Unlike other scenarios considered by this author, Charlotte was largely isolated from these elements throughout her childhood and adolescence, with such isolation coming from her poverty-stricken background and her Christian upbringing. To the extent she was sheltered from such dissolution in a way her peers at Dupont were not, many might expect her to show greater resilience when immersed in such an environment. This was not the case. Her stated values upon enrollment crumbled after a few short months or weeks even. It is true that she does not succumb to the sort of hyper-promiscuity exhibited by many of her peers, but she does yield and succumb, in very profound ways, to the cultural norms that engulf her.

◊

Both Can’t Buy Me Love and I am Charlotte Simmons are highly recommended by this author. Neither however are perfect, as it is impossible to regard either as a cinematic or literary masterpiece. There are some aspects of Can’t Buy Me Love that seem silly, including the “African Dance” scene. Overall though the film makes some profound observations about human nature and male and female sexuality that are not often found in any narrative. In this way, the movie is far more insightful than many other, better known teen movies of the 80s, particularly various John Hughes films like Pretty in Pink or Sixteen Candles. This movie does not have anywhere near the comedic chops of Sixteen Candles or Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, but that is more than made up for by the profound psychological insight it offers. The film also serves as a nice reflection of the fashion and times in 1987. Some viewers may be incredulous of the ending. The ending does seem highly improbable, but a more realistic, “downer” ending just would not succeed with most audiences.

Can’t Buy Me Love generally does not have the star power of other 80s teen movies, including Matthew Broderick as Ferris Bueller or Annie Potts as Andie’s older friend Iona, to say nothing of James Spader as the archetypical villain in 80s teen movies, Steff McKee. John Cryer as “Duckie” is beyond annoying and one wonders what the appeal of both actor and his character could be. Amanda Peterson is far superior as a leading actress however, in acting, charisma, and physical beauty. Watching Amanda Peterson in her role is disturbing in one important respect, however. She was (allegedly) raped or sexually assaulted sometime around the timeframe of when this movie was filmed, was set to be an a-list star from the success of this film. To-date the alleged perpetrator has not been named let alone charged, but one can imagine such individual to be of a similar gestalt to Harvey Weinstein. Eventually dropping out of Hollywood, she succumbed to drug addiction and other problems and died somewhat recently. Just shy of her 16th birthday at the time of filming, her tragic beauty is immortalized in what is now a lesser-known film.

Charlotte Simmons receives the very highest recommendation, even though it is a most imperfect novel. Some aspects of the narrative defy credulity, including the notion that an American student in poor Appalachia could develop proficiency in French to be able to read Flaubert’s Madame Bovary in the original, as a product not just of American public high school overall but a public school in poor Appalachia. Young women like Beverly, whose father was a CEO at a fictional insurance company called “Cotton Mather Insurance Company,” do not generally stay in dorms, but belong in sororities. There are of course outliers. Another sub-plot is that JoJo is worried at his prospects of making it into the NBA as Dupont has recruited a black freshman prospect that the coach intends to start instead of JoJo, benching the only white player. Rather than being benched, a student athlete of his prowess would assuredly transfer elsewhere, particularly as the narrative indicates he is a good basketball player. There are other flaws in the novel, but, despite the number of negative reviews overall, Wolfe shows true insight into human psychology and male and female sexuality in particular. His novel reveals hidden truths about female desire, unlocking a breakthrough technology for younger readers coming of age that revolutionizes the reader’s understanding of female sexual attraction and psychology.

Above all, Wolfe offers a searing, irrefutable indictment of our education system. Dupont (hint Duke) University is shown to be a sordid, debauched playground for mostly rich, affluent white college kids, thrown together with a grab bag of diverse genetic party favors, a sordid playground revealing most college students to be anything but scholars, a glorified babysitting service whereby the affluent binge-drink and fuck while idolizing the basketball team (or in most instances the football team as well). He also exposes how this country has allowed its university system to prostitute itself out, like a shameless whore, to the NFL and NBA. Written 20 years ago, this attack on higher education was before the student loan crisis and the most recent wave of far-left Cultural Marxism became the pressing issues that they are now regarded as. And whereas most tepid, limp-wristed conservative punditry disparages the idea of college and humanities in particular, Wolfe attacks the institution of American higher education from an entirely different, more enlightened perspective, exposing the abject Philistinism and debauchery that pervades American campuses, something most mainstream conservative punditry is utterly uninterested in.

Both the film and the book in question offer valuable insight into human psychology, as well as some troubling aspects of female sexual attraction. In many ways these works expose Nietzsche’s concept of the herd mentality. So many people follow along with what everyone does. Many aspects of both narratives are incredibly grim. It is unpleasant to think about a young woman like Charlotte Simmons, who carries herself as a good Christian girl and blathers on about wanting “the life of the mind” only to fall in line all too quickly with the abject philistinism and debauchery that pervades American college life. Reading how the very process of attraction begins to unfold for Adam, only to be completely short-circuited and undone because of peer disapproval, is incredibly distressing. Both handsome and intelligent, Adam might have been branded as an “incel” by some of Charlotte’s peers if that term has been invented before 2004. That component of the narrative and how it reveals the key, critical component of social proof in female sexual desire defies certain stereotypes with what has become a lazy, cliched insult blurted out every second by automaton, NPC sorts on twtitter, reddit, and the like. Both the book and film are infused with moments of humor, although Wolfe’s sardonic wit is without compare. Even though both works are likely unfamiliar to many, both make very important observations and impart true insight not often found in literature or cinema. And it is for that reason that both are indispensable.

Ms. Dallas’s numbers are somewhat confusing. The forty percent figure would have to pertain to the nearly 60-40 ratio of women to men at Chapel alluded earlier in the text, ie the entire student body population of men and women. Do the ten and twenty percent figures pertain to the overall student population, or does she mean ten and twenty percent out of the entire male student population?

The ten and twenty percent referred to in Ms Dallas numbers are of the entire male student population. It's fairly well known that women regard 80% of men as below average, so her numbers are right in line with that.