A key, defining distinction between the left on one hand and most expressions of mainstream conservatism on the other is the left actually understands the nature of power. Moreover, unlike mainstream conservatives, the left has exhibited a willingness to gain power and use that power once it is both available and has at least the promise of achieving desired ends. The left have no qualms about compelling those they disagree with to submit to their ideology; “bake the cake, bigot,” “make the floral arrangement, bigot,” and so on. The left has no reservations about compelling parents to comply with harmful transgender ideology (as seen in California, Colorado, and other states, as well as Canada). Admittedly, the left may have overextended on this particular issue1, but on the whole, in the long-run, their understanding and application of power, as an expression of moral conviction and political will, has proven remarkably succesfful overall.

Conversely, far too few conservatives, if any, would support, for example, government intervention to stop deluded parents from inculcating their sons and daughters with transgender ideology and radical gender theory. This derives in part from a fear that most child protective services and other government agencies are subject to political capture. At the most basic, fundamental level, however, it stems from a categorical aversion to the use of such power under any circumstances, regardless of who is in power. Indeed, conservatives often balk at using the power of the state in such ways, even in the reddest states where government authorities have not been so corrupted.

This key, critical difference is arguably most pronounced in so-called free speech issues and first amendment jurisprudence. The left seek to significantly constrain the scope and breadth of first amendment protections in ways that advance their political and ideological objectives, as seen in increasing numbers of leftist thought leaders and politicians advancing the idea that so-called “hate speech” should receive little or no first amendment protections at all. Such utterances are routinely exhibited in academia, mass and social media, as well as left-wing politicians.

One of the advantages wielded by the left is their understanding that not only are first amendment protections far from absolute, they necessarily ebb and flow with changing norms and mores of a society and civilization that has undergone drastic—and very harmful—changes since the end of World War II. The left are entirely wrong about the ideological and normative objectives they seek to advance. However, these leftist tendencies nonetheless reveal greater insight about the nature of power and certain abstract principles about power as an expression of moral conviction. While the left are absolutely wrong about the ends they seek to achieve, they are fundamentally correct—at an abstract, philosophical level—in relation to the means and methods they employ to achieve those ends. If any meaningful opposition to the left can ever hope to be achieved, these insights must be adapted by a new, right-wing opposition that supplants and replaces mainstream conservatism with a far more radical vision that understands the nature of power and embraces a willingness to use such power.

This realization has been open and apparent to this author for many years, but was brought in even sharper relief during the research and writing of “Pornography and the Failure of the Constitution.” The research and writing process uncovered a legal tract by Amanda Shanor, entitled “First Amendment Coverage.” The central thesis of this law review article is “‘that the determinative factor whether speech or expressive activity ‘falls within the First Amendment’s reach and what is excluded from it does not rest on the distinction between speech and conduct,’ but rather on ‘social norms. . ..’” (Shanor quoted and summarized in “Pornography and the Failure of the Constitution.”) Shanor argues in pertinent part:

The First Amendment does not extend when there is a common norm about the social effect of the activity or when the court decides there should be such a norm. Conversely, when there is no such common norm—or the court decides there should not be one—the First Amendment extends. (346)

In order to properly assess these claims, certain preambles must first be established. First, Shanor is a Jewish lesbian of the most insufferable sort. Shanor is a graduate of Yale Law School and Yale College, and a PhD candidate in law at Yale University, and currently works as an assistant professor at the University of Pennsylvania Wharton School. Notably, she has worked on the legal team of the American Civil Liberties Union on the Masterpiece Bake Shop matter, working to compel citizens to “bake the cake, bigot.” She has regularly spoken at various federalist society events to speak on behalf of the legal work and social policies she espouses. More mainstream readers may object that noting her Jewish heritage and sexual orientation is ad hominem, but her identity, background, and “early life” profile match strong trends observed by Kevin MacDonald and others who have observed a collective propensity among Jewish individuals to advance insidious, leftist ideas that are tantamount to racial suicide and civilizational ruin for Europe and the West.

Any understanding or assessment of Shanor’s thesis also requires a brief summary of the chilling effect doctrine of first amendment jurisprudence. Knowledge and familiarity with this doctrine is a critical component in understanding whether current constitutional law and received orthodoxies about The First Amendment are at all coherent or defensible —both as a legal proscription against government censorship and as an important normative, social value. The chilling effect doctrine dictates that the First Amendment does not merely apply to outright government censorship. Rather, it applies to any law, regulation, or other governmental action that could have a “chilling effect” on speech and expressive activity, particularly speech the government disfavors or is perceived to disfavor. The rationale is that laws that sweep too broadly or are unnecessarily broad in scope unduly restrict speech that should not be prohibited. Similarly, vague or overly broad laws deter people from speech and expressive activity that could conceivably be perceived—in error—as falling within a legal prohibition or constraint. In order to survive a challenge to the constitutionality of a law or regulation on the basis of this chilling effect, first amendment jurisprudence dictates that the government must show that the law or regulation advances either an important or, in most instances where a law is not “content neutral,” a substantial state interest, and that the law does not suffer from overbreadth or vagueness, i.e. the law could have been drafted and tailored more narrowly to avoid or reduce this chilling effect. It is on the basis of overbreadth and vagueness that many sensible laws have been ruled as unconstitutional, most notably the ruling in United States vs. Stevens that invalidated a law prohibiting the production, dissemination, and sale of dog-fighting videos and other materials depicting animal cruelty and cruel and gratuitous killing of animals. After the original law was struck down, the law was redrafted, focusing only on sexual crush videos. The practical result of the Stevens ruling could not be more appalling; although dog-fighting is illegal in all 50 state, videos or images depicting dog fights or the “training” of fighting dogs with cats as bait cannot effectively be proscribed under the current, controlling interpretation of The First Amendment.2 The series of Ashcroft decisions 535 U.S. 564 (2002) and 542 U.S. 656 (2004), which struck down legislation which sought to criminalize simulated sexualized images of a minor on the basis of overbreadth, chilling effect, and even vagueness, are another example of how stringent application of this doctrine invalidates sensible and even necessary legislation. See also Reno v. American Civil Liberties Union, 521 U.S. 844 (1997)

In “First Amendment Coverage,” Shanor argues that, rather than some coherent application of First Amendment protections that is categorical and consistent, the degree to which the First Amendment protects—or does not protect—free speech ebbs and flows with changing normative values and societal norms. She cites an important Title VII case Harris v. Forklift Systems, Inc, in which the owner of the business concern made disparaging remarks to a female employee. Some of this was of a sexual nature and even amounted to a quid pro quo, but some of his actionable comments simply expressed his (somewhat reasonable) belief that women should not work as forklift operators as well as other comments that go to the heart of matters of gender roles and the differences between the sexes. Shanor notes that the brief included substantive arguments that Title VII violates the First Amendment on this very “chilling effect” rationale described above. These arguments were not even addressed by the Supreme Court. Shanor argues that our legal jurisprudence has simply made a value judgment that there is a “social interest in equality and anti-discrimination.” While legal jurisprudence has no concerns about how t-shirts with the word “fuck” written on them or the ability to flip off law enforcement or anyone else degrade “civil interactions,” that same jurisprudence does value “the ability to have workplaces that are organized on civil interactions,” even removing the workplace as “a place of ideological contest.”3 Rather than being seen as the viewpoint discrimination it obviously is, such exercise of power by the state simply ensures all working environments are “governed by… norms and practices appropriate to a modern workplace. . .” (357). A more accurate statement would be a working environment governed by the “norms and practices” that the left deem appropriate, a standard that has only become more stringent and oppressive over time.

How So-Called Civil Rights Laws Are Antithetical to Free Speech Norms

These and other examples submitted by Shanor in support of her thesis implore considering what ways government action has a remarkably chilling effect on “free speech.” Title VII and other arms of civil rights laws provide a most immediate, obvious example. It is admittedly the case that in order for an employer to be in violation of Title VII, comments and behavior by employees (or even a manager and owner) have to be “severe and pervasive.” But because any actor in the commercial sphere always seeks to be well within the law so that even the prospect of litigation is as remote and unlikely as possible, the practical effect of these laws compels employers and business owners to police what employees say, what they wear, the artwork or images they display in their working spacesand other matters with particular focus and zeal. Professor Eugene Volokh summarizes the legal advice any competent legal counsel typically gives to such clients on this matter. He first cautions that because words like “severe,” “pervasive,” “hostile,” and “abusive” are inherently “vague,” there is no real way of knowing if a particular set of facts rises to the level of actual liability “until it gets to court.” He elaborates further:

As one state administrative agency frankly acknowledged, “one person’s discussion may be another person’s harassment.” And because of this, the safe advice would be: “Shut the employees up.” After all, the typical employer doesn’t profit from its employees’ political discussions; it can only lose because of them. The rational response is suppression, even if the lawyer personally believes that the speech probably doesn’t reach the severe-or-pervasive threshold.

These legal standards have in turn promulgated the cultural and sociological phenomenon of human resources departments, staffed almost exclusively by a particular sort of woman and (usually) gay effeminate male, and the modern working environment where the more prudent individuals conscientiously discern fellow co-workers as “not their friends.” Title VII does far more than deter a machinist, mechanic, welder, or other blue-collar worker from posting a Penthouse centerfold or even a woman in a bikini at his work station or making a crude sexual joke, just as it goes well beyond deterring a lewd comment about another woman or the female anatomy during water cooler or break time banter. It effectively precludes any controversial but high value speech about the nature of men and women, gender roles, and a wide range of other issues. It does this not just at work settings but any setting or context connected to those with whom one works. Such examples would include parties or get-togethers in the evening or at the weekend, social media, and so on.

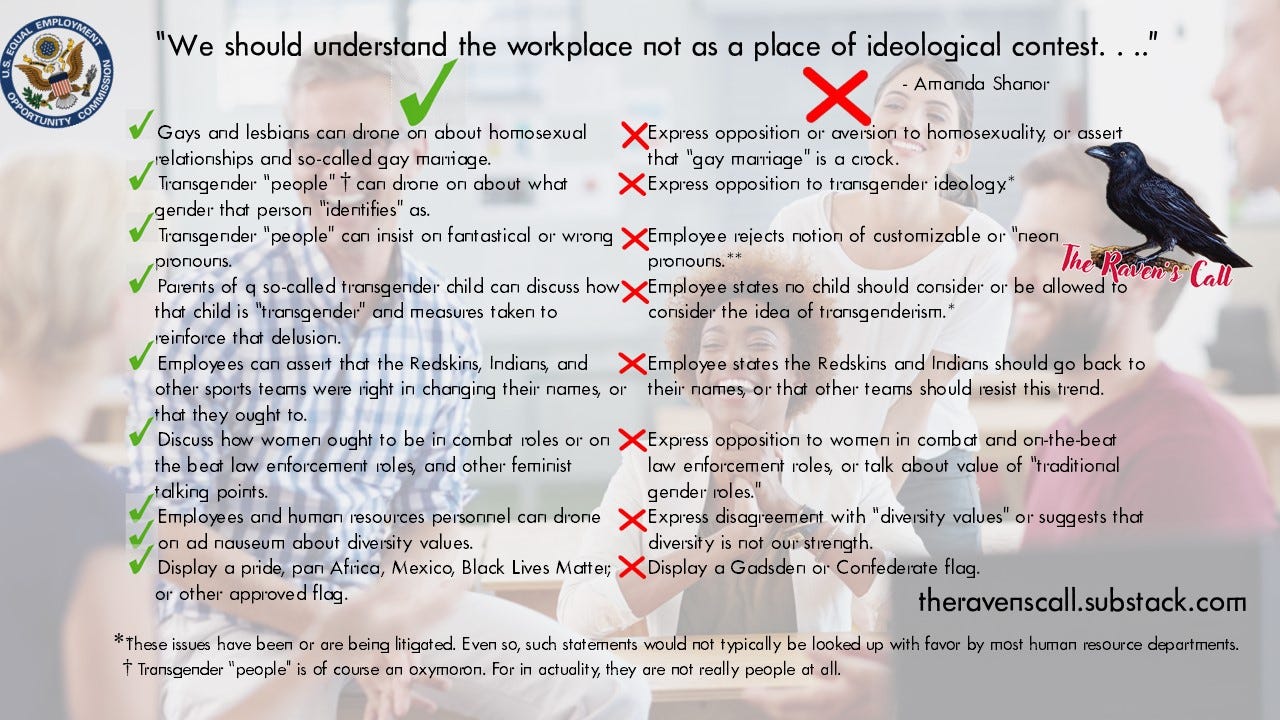

Quite remarkably, the Equal Employment Oppurtunity Commission (EEOC) has found merely wearing confederate t-shirts—and the employers delay of two months in prohibiting such attire—was sufficient to sustain a hostile working environment claim. Even more shocking, the same entity also found that attire displaying the Gadsden flag, replete with the motto “Don’t Tread on Me” was also sufficient to state a claim for a hostile working environment. Significantly, the complainant stated that “he found the cap to be racially offensive to African Americans because the flag was designed by Christopher Gadsden, a ‘slave trader & owner of slaves.’” This standard could preclude any images of or discussions about most founders of this republic from being the safe harbor of approved of subject matter in the workplace.

Furthermore, it is doubtful whether the EEOC or other governmental body would consider apparel depicting Black Lives Matter, the African American flag, the Pan Africa flag, or the Mexican flag as creating a hostile working environment for whites. Similarly, whereas a lawyer or other white-collar worker would be able to display a model of a P-51 mustang or spitfire in his office, it would be unwise to display a Messerschmitt 109 or Focke Wulf 190, even if complemented with their Allied counterparts. Professor Volokh notes how this effectively prohibits a wide range of unobjectionable content, from impressionist nude paintings, to a picture of a man’s wife wearing a bikini.4

The same principle applies in Title II, which governs public accommodations in restaurants, hotels, and the like. The proprietor of a restaurant, hotel, or other public accommodation would be well-advised not to engage in any speech or other “expressive activities” that could make “protected classes”—that is racial minorities, women, gays—feel unwelcome. The universe of speech, sometimes referred to as “expressive activity” in legal parlance, that could make protected classes feel unwelcome is truly vast. Irrespective of social norms and taboos that have risen with liberal cultural and institutional hegemony, the proprietor of any establishment open to the public would be unwise to don a confederate banner of other paraphernalia asociated with the Confederacy or Southern heritage or have any imagery, art, or signage that could be interpreted as discriminatory or disfavoring certain protected groups. Such a proprietor would also be well advised to never discuss matters of race, gender roles, and a wide range of other topics in order to insulate himself from liability under both Title II and Title VII. A veteran or former service member who rightly decries women in combat roles, coed barracks, or women in “on the beat” law enforcement roles best keep his mouth shut, even if he owns the business, because a customer or employee alike could take umbrage.

Discrediting the notion these laws simply regulate modern workplaces so that they are free from “harassment” or other speech the government disapproves of, both Title II and Title VII provide a strong incentive for business concerns, both as employers and as proprietors of public accommodations, to enforce these onerous speech codes not just on employees, but on the public at large. Professor Volokh notes in another article that if the EEOC is correct about apparel depicting confederate flags as sufficient, by itself, to state a hostile working environment claim, then restaurants and other employers offering public accommodations would be subject to claims under either Title II and Title VII for not applying the same standards to the general public who seek to patron a given establishment. He writes in pertinent part:

Employers also have such a duty whenever they are engaged in by patrons and an employee is offended, since employers have a duty to prevent “hostile work environments” created by patrons. Bars and other places of public accommodation would also have a similar duty not to display Confederate flags and similar imagery, and to eject patrons who do the same, so long as a patron complains that he is offended.

The mandate for employers offering public accommodations to police speech or expressive activity among patrons as well as employees could be truly staggering. A waitress could demand that a patron be evicted for wearing branding from Playboy, Hustler, Pornhub, not necessarily a bad result if it were coming from the right, but surely in contravention to first amendment and “constitutional principles” mainstream conservatives drone on about. Someone who recognizes or knows that the Death in June symbol is derived from the SS Totenkopf could demand a proprietor to evict a patron for wearing such a t-shirt (or complaining about an employee wearing such a t-shirt in a place of employment with a casual dress code that allows t-shirts, and even band t-shirts). These body of laws could invoke liability at an employee or patron wearing a Feindflug garment themed after the song “Stukas im Visier” but not anti-white, militant rap music such as “Fuck tha Police.” Many may rightly object that no one should wear band t-shirts or the like in a work setting, even one with a casual dress code, but if one employee is allowed to wear a Nirvana shirt and another is allowed to wear an NWA t-shirt, then a person who shares this author’s taste in music should be allowed to wear similar attire expressing affinity for edgy neofolk and industrial music acts.

So-Called Hate Crime Laws and Their Effect on Dissident Views

The rise of so-called hate crime legislation over the past 25 years is another example of government action that deters, in powerful ways, speech and expressive activity the ruling class dislikes. Although hate crime legislation does not ban or censor disfavored types of speech per se, it does create a prohibitive chilling effect in two important ways. First, the element of so-called hate speech can create vastly disparate outcomes in otherwise very similar or even otherwise identical fact patterns. This can be the difference between full exoneration, or even a decision not to prosecute at all on one-hand, and the most severe penalties available with so-called hate-speech enhancers on the other. As a hypothetical, consider two scenarios where a white man sits at a bar or is otherwise going about his day. Words are exchanged with a black or other racial minority. The racial minority lunges at the white man or otherwise commits an assault or even assault and battery in a manner that causes the white man to have a reasonable fear of death or serious bodily injury, entitling him to a claim of self-defense. The white man defends himself, resulting in either serious injury to or death of his antagonist. In one instance, the white defendant has never indulged in so-called hate speech. Nor does he utter any forbidden words. In the other, he has read, or even simply has copies of books and materials on matters of race or the Jewish question (as does this author), writes about such matters (as does this author), or simply listens to Death in June (as does this author), owns German World War II militaria (as does this author) or likes skinhead oi music (one album by English Rose is pretty listenable), or even perhaps uttered a racial epithet while defending himself. It is totally foreseeable that whereas the first instance results in an acquittal or even not even having charges filed at all, the second instance could result not just in a conviction, but conviction with enhanced “hate crime charges.”

There are real life examples of this. The trial and conviction of Gregory and Travis McMichael for the death of Ahmaud Arbery, in which the black went for the shot gun, went from what ought to have been a case of self-defense to a conviction on murder charges in state court. In addition to the fact the McMichaels are white and Arbery was black, the McMichaels’ views about race—crude, although not unreasonable—were the prime, motivating factor. The Georgia citizen arrest statute was arcane, as it has since been repealed, but it did seem to grant the McMichaels authority to conduct a citizen’s arrest. The McMichaels were convicted, and later even convicted on separate federal hate crimes and civil rights charges for good measure. It is of particular note that in preparation for the federal hate crimes and civil rights prosecution, the government scoured their smartphones and other devices for speech that the government and other powerful interests disapprove of.

Another example is the Nicholas Minucci prosecution and conviction. Minucci was convicted and sentenced to 15 years incarceration for uttering a racial epithet when intervening to stop a car theft. This was in the context of a crime wave that had afflicted his neighborhood in Howard Beach, in Queens New York. Minucci used a baseball bat in the altercation, but asserted that the perpetrator attacked him for intervening in a crime. It is also of note the prosecution did not charge Minucci for attempted murder, which no holds barred use of a baseball bat, a lethal instrument, would usually entail. While far less sensationalized than the McMichaels case, as the father and son are less than entirely sympathetic defendants given their propensity for crude, vulgar expressions, the Minucci case exemplifies anarcho-tyranny in an even more striking manner than the McMichaels fiasco, although both share some striking similarities. A black man is caught in the commission of car theft, a good Samaritan, Minucci, intervenes, defends himself, and is convicted and incarcerated for the trouble—all because he uttered an insult.

Consider further that Austin Metcalf, who was murdered in cold blood at the hands of Carmelo Anthony, was at one point alleged to be a “white supremacist.” These claims were debunked, but readers can infer that had some of these claims been proven to be true, the chances of Anthony avoiding justice would become prohibitive if not a foregone conclusion, not just because of normative taboos in mainstream society so utterly misguided, but because of how the prosecution and other governmental agencies would then handle the matter. This suggests that if a person, such as yours truly, were murdered by a racial minority, the perpetrator would likely get away with murder on the basis of the victim’s politics or ideology. This means that anyone who expresses views such as those espoused in this publication assumes the risk of unfair prosecution and conviction in what would otherwise be a valid claim of self-defense, as well as the risk that bodily injury from an assault or even murder would not be fairly prosecuted under the law and the principles of “equal protection under the law.”

The much greater motivation prosecutors have in charging those like the McMichaels, Minucci, or the hypothetical to abovee ought to invoke constitutional claims under the equal protection clause for selective prosecution and other theories. But as with so much rhetoric concerning constitutional rights, such assurances are hollow. The government in power and the legal system in place have no qualms about such disparate treatment based on political or ideological viewpoint. Indeed, it is of note that courts summarily dismissed selective prosecution claims brought by January 6 protestors on the novel theory that far more destructive and violent Antifa and BLM “protests” were different because they did not happen during the day.5

These examples are just the tip of the iceberg. Another example concerns Sophia Rosing, who was sentenced to 12 months in jail for what would otherwise bw unremarkable drunken behavior by a co-ed, except she uttered racial slurs and became a target of cancel culture. She was recently denied parole.

There are other ways federal, state, and local governments punish speech it disapproves of. Consider that most municipalities make no effort at all to enforce laws against vandalism and graffiti, and yet if one were to carve or paint a swastika on a park bench or place a sticker featuring the confederate banner or a World War II Reichskriegsflagge on a park bench or some fixture in public transit, a special hate crimes task force would be assembled to find who did such a dastardly thing. In some instances, in bedroom communities outside of New York City (Westchester and Long Island), police authorities have launched publicized hate crime investigation for the distribution of leaflets they do not like.

Having Forged a Somewhat Softer Tyranny

These examples and many others besides6 have created a regime of soft or even not so soft censorship that pervades many aspects of American life. In addition to deterring employees, managers, and even business owners from comments on matters of sex, race, and other important issues, the same considerations that apply in the work setting also apply to social media and any other context that is related or could be related to one’s coworkers. Any person who is not independently wealthy, and even those who are, would be foolhardy using a real name while expressing perceived heresies against received orthodoxies about race, sex, and so on. This is very much in the consciousness of any sane person with a functioning level of intelligence. This has created an atmosphere defined by self-censorship and second-guessing, and much of this has been advanced by laws, regulations, and various policies advanced by the governmen. Most astonishingly of all, the judiciary has even stated this is its naked intention:

[W]hile [Title VII does] not require an employer to fire all "Archie Bunkers" in its employ, the law does require that an employer take prompt action to prevent such bigots from expressing their opinions in a way that abuses or offends their co-workers. By informing people that the expression of racist or sexist attitudes in public is unacceptable, people may eventually learn that such views are undesirable in private, as well. Thus, Title VII may advance the goal of eliminating prejudices and biases in our society. Davis v. Monsanto Chemical Co., 858 F.2d 345, 350 (6th Cir. 1988).

In some ways, the fact that the ruling order is not as heavy-handed as say die Stasi was during the existence of the GDR (aka East Germany) makes it that much more onerous. East German patriots and dissidents knew who and what they were dealing with, knew they had to be careful about whom they confide in. Most Americans have at least some inclination about this, but far too many are deluded into thinking that this is actually a free country that embodies free speech values in the ways school children are taught in civics class. Just as an enemy that is well camouflaged or difficult to detect is that much more dangerous, those who are enslaved, imprisoned, or otherwise lack freedom but perceive themselves as being free have no hope of emancipating themselves.

In this panel discussion, Shanor tries to qualify concerns about the government deterring—or even sanctioning—expressive activity it disfavors as being relegated only to commercial activity. First, it is of note this is a much more limited statement compared to the bolder assertions in the New York Law Review article discussed above. Beyond that, this is small solace for the vast majority of persons who are not independently wealthy. Small business owners typically spend an exorbitant number of hours in their business (some small business owners even live on premises, in a back room or in a loft above the premises). Beyond that, it draws on Anglo-American naïveté about free will and what it really means to be subject to material needs. A person who must procure money to pay rent or mortgage, buy food, and meet other needs is not, in fact, free to simply quit the very means that allows him to fulfill these basic needs. In relation to Title VII and Title II, Shanor and others simply aver that government suppression of speech it disfavors and dislikes is commendable because it advances their ideological and political ends, couched in terms of promoting a working environment and public accommodations free from “harassment” and “racial hostility.” This begs the question why deterring and eradicating off-color or controversial remarks in workplace settings is a “substantial state interest,” but doing something about pornography and the many social harms it imposes is not.

As Professor Mark Rienzi articulates during the question-and-answer portion of the same panel discussion, it is fairly obvious that public accommodations laws are being used as a way to compel speech and cripple political opponents in the modern era in a way they were not in the first such civil rights cases in the 1960s. In the past, “nobody actually thought to try to use public accommodations laws to make the racist baker bake the cake for the [interracial] wedding because people didn’t really want the racist. . . baking the cake for their wedding.” It is only in the modern era that it occurred to leftists to “take the government and wield it as a club to crush [an] opponent into oblivion.” Indeed, “public accommodations law” goes “beyond one side winning a political fight over what the rule should be.” It is now about “using the power of government to force people to bend the knee or force people to get with the program and say the thing the government wants” them to say.

Recall the earlier account of Shanor’s blithe rhetoric about how these onerous civil rights laws remove the workplace as “a place of ideological contest,” a rationale also extended to public accommodations. Any sensible person knows this is not true and that the removal of any “ideological contest” only goes one way. Or perhaps it is more accurate to assert such environments are indeed removed as a “place of ideological contest” because these are spaces where only leftist orthodoxies dare be uttered. Anyone with firsthand knowledge of office working environments knows how many coworkers feel they have carte blanche license to pontificate endlessly about Donald Trump’s presidency, as long as such commentary is as negative and as hysterical as befitting “Trump derangement syndrome.” No one of any sound mind dares push back, and indeed the failure to express agreement can tip off leftist busybodies that someone dissents. Human resources departments and corporate America as a sociological phenomenon have free license to drone on endlessly about leftist talking points concerning “diversity, equity, and inclusion.” By the same token, any eating establishment or other concern subject to public accommodations law has free rein to fly gay pride flags, celebrate and push so-called “pride month” in the most obnoxious and ostentatious manner as possible. The owner of an establishment who does not agree with these things however is not free to express his opposition. In this way, the enforcement and promulgation of these standards by the government render ideas and expressions that comply with these standards as the mainstream, and any stated opposition or dissent as deviant. A gay co-worker can freely discuss his so-called gay marriage at work, while persons who rightly balk at the very idea of so-called gay marriage must remain silent. In this way, talk about gay marriage becomes garden variety water cooler banter, whereas opposition to it can only be uttered in hushed whispers. This makes gay marriage mainstream and unremarkable, and opposition to it as something not always suitable for polite company. The same applies to transgender lunacy. If a co-worker can harp incessantly about how that individual is transgender, or how a son or daughter is transgender while everyone opposed is effectively muzzled from even daring say a word in opposition, such a regime normalizes transgenderism while relegating opposition to it in the same category as crude sexual jokes or innuendo.

One must also consider how radical a proposition civil rights laws really are, at least for individual persons7 who own businesses and retain employees. This excerpt of a concurring opinion by Justice Sandra Day O’Connor further demonstrates that the idea that this is a free country is a sick joke:

“The Constitution does not guarantee a right to choose employees, customers, suppliers, or those with whom one engages in simple commercial transactions without restraint from the State… When an organization’s activities take on a commercial character, its associational choices are subject to legitimate state regulation, particularly when those choices result in discrimination prohibited by law.” (468 U.S. at 637)

The employees a business owner chooses (or does not choose) to hire and work with is much more than a commercial transaction, but is government coercion that forces individuals to spend at least a third of one’s time, likely more given how hard and time intensive owning a business often is, with persons that that business owner may find unsavory or undesirable.

Perhaps That Which Violates First Principles Should not Be Tolerated at All.

There are many other conclusions that emanate from these considerations. It is very likely that Shanor’s thesis is correct, to at least some degree, that the practical application of First Amendment jurisprudence is not buoyed by some categorical commitment to free speech values. Consider further the novel suggestion or conclusion that no government body or society could ever hope to not limit or censor speech in various ways. Before the cultural revolution of the 60s, of which the Supreme Court was a key catalyst, as evinced for example in Cohen vs California decision, there were no qualms about imposing legal sanctions on not just obscene speech but profanity as well. One hundred years ago it would have been unthinkable that someone would walk around with a t-shirt with the word “fuck” on it; indeed, it would be unthinkable that people would dress so slovenly irrespective of what slogans or captions are featured on a garment. In the modern world, anyone can peruse any novelty shop in most urban settings and a large selection of garments have profanity written on them. (Most readers are doubtlessly aware of a certain type of novelty shop, the sort that has bongs used for marijuana but are sold with disclaimers that no such use is intended and typically have a section devoted to sex toys, lingerie, and the like).

Going beyond that, there is a more radical realization to be discerned that perhaps free speech should not be the high societal and normative value that many hold it to be, particularly if and when a far-right, populist movement gains and consolidates power. Aside from pornography, which is correctly viewed as a sort of ersatz prostitution, a sexual aid, and an activity that is inherently commercial and transactional in nature8, the notion that all utterances, including those in violation of first principles and a firm moral conviction should be tolerated and permitted is most dubious indeed. The result of the Stevens case is that the First Amendment—or rather how it has been interpreted by the Supreme Court and lower courts—prevents the government from doing anything about text, photographs, and videos that glorify or justify animal cruelty and needless killing of animals for sick personal gratification. Even though dog-fighting and using cats as bait to train fighting dogs is illegal in every state and jurisdiction in the country, our esteemed judiciary has made it impossible for the legislative branch to draft and promulgate any body of legislation that would correctly ban such vile material. There is no value to speech that justifies, condones, or excuses animal cruelty of that nature. And not only does that instance further convince the more enlightened to reject the First Amendment not just as a legal proscription but as a normative value, it also demonstrates that perhaps the 8th Amendment prohibition against cruel and unusual punishment is also a mistake.9

By the same token, why should speech that extols transgender nuttery and lunacy be tolerated at all? Such intolerance of transgender ideology should apply not only when this insidious ideology targets children and minors. Rather, I submit such utterances demand utter and absolute intolerance in all circumstances, even if merely directed at adults. Anything less allows these ideas into the stream of culture, which will necessarily entail exposure to children and adolescents alike.

Blood, race, and soil are properly discerned as the hallmark of both a civilization and a cohesive society where members of that society coalesce around each other, and derive meaning, community, and belonging from shared blood, race, and soil as well as history, language, and even religion, or at the very least religious tradition. Once blood, race, and soil are embraced as the highest values, why should speech or more particularly commercial speech such as advertisements and mass media promulgated by Hollywood and big recording labels promoting race-mixing and multi-culturalism not be subjected to censorship and banning? In lieu of outright censorship, the tactics of soft censorship that, while not outright banning disfavored speech, stigmatizes and sanctions it in various ways might admittedly be more effective for reasons set forth above.

Just as those elements currently in power blithely assert that it is a governmental interest to remove any semblance of what that order regards as distasteful, unsavory, or unwelcome, it is no less reasonable for the populist right, should it seize and consolidate power, from making similar assertions on a great many issues, from animal cruelty to race-mixing and the chimera and lie that is the modern American vision of multi-racial multiculturalism. That, among other things, is of course what the application of state power and even state violence is in many instances—an expression of moral conviction by those who have gained power and wield it. The left has understood this for decades, while far too many mainstream conservatives drone on about meaningless principles, and how their ideological enemies have rights.

A scenario whereby the populist, reactionary right has achieved political and cultural hegemony does seem remote, far off in the distance of the future. However, any problem, no matter how seemingly intractable, starts with the first steps involved in understanding the problem for what it is intrinsically. In this instance, it begins by recognizing and discerning how the left use power to curtail and suppress the expression of political and ideological positions it deems unsavory. This is coupled with the obvious truth that no governing entity could ever hope to be truly neutral in how its laws are drafted or applied, and how such laws deter or even restrict speech. Even setting aside the most obvious exceptions like threats, extortion, bribery, fraud, and so on, free speech absolutism is a dream and a chimera. The left understands this with a shrewd cynicism, whereas too many mainstream conservatives not only cling to this impossible ideal, but appeal to their ideological and political enemies to fight by these arbitrary and impossible standards. Correcting this error requires true opposition to the left to understand how these standards are impossible and cease to fret about it.

PLEASE NOTE: Readers who appreciate the insight and perspective set forth in this essay are urged to consider offering a paid subscription or even a founding member subscription, provided such expenditures are not unduly burdensome. Readers who enjoyed this article and found it informative and insightful are also encouraged to signify their favor for this and other writings by clicking on the “like emoji,” as well as sharing this and other articles to those who would find this and other essays and articles interesting, insightful, or provocative. The like emoji or lack thereof is a greater factor than it should be that readers unfamiliar with an author or publication use to decide whether to read any particular piece or not.

Follow Richard Parker on twitter (or X if one prefers) under the handle (@)astheravencalls. Delete the parentheses, which were added to prevent interference with Substack’s own internal handle system.

Particularly given how Trump’s “they/them” advertisement was a key factor in his historic comeback and other instances of pushback, the left seem to be losing on the transgender bit, for the moment. Caution is in order however as some foolishly thought the Republican revolution in 1994 and other cultural and political developments in the mid 90s signaled the end of “political correctness.”

See the discussion in “Pornography and the Failure of the Constitution.” The discussion on this matter reads in pertinent part:

Indeed, a special report by the New York State Animal Law Committee determined that "This [revised] statute limited its proscription to so-called crush videos, the fetish animal torture videos designed to appeal to prurient interest." The revised statute was deemed constitutional in a 5th circuit appeals court decision Texas vs Richards No. 13-20265 (5th Cir. 2014), in which defendants were prosecuted and later convicted for producing and selling videos in which kittens, chickens, and other animals were tortured and killed in sexually orientated crush videos.

In order to fend off any accusations of splicing quotes in an unfair or deceptive manner, the sentence in questions reads as follows: “We should understand the workplace not as a place of ideological contest and communicative uncertainty—like the paradigmatic realm of political speech—but instead as a space governed by norms and practices appropriate to a modern workplace, in which harassment is inappropriate and causes disruption and harm.”

Instances like this should include a visual depiction of what is involved. A picture of a woman in a bikini entails a wide range of possibilities, including a wet bikini displaying a woman’s nipples and the outline of her vulva, to a rather innocuous photo from a beach side vacation.

Equal protection claims by January 6 protestors were rejected by courts, but this simply impugns and discredits our legal system all the more. One rationale used is that there was no disparate treatment by similarly situated defendants, distinguishing the attack on the Federal building in Portland Oregon because it happened at night. United States v. Judd, 579 F. Supp. 3d 1, 7–8 (D.D.C. 2021). Those readers who do not hate this dystopic abomination s of country with every last fibre of their being are reminded once again: Ask not what you can do for your country, ask what your country did to you: in this instance, pissing on our hands and telling us it’s the rain.

Another example is how the government radically sanctions speech in its body of labor laws.

One possible solution that would reconcile concerns with individual liberty and mainstream considerations dissuading discrimination in the workplace and public accommodation lies in dispelling the legal fiction that a corporation is a person. A subject for a future essay, distinguishing between actual individuals and corporate entities would allow for compulsory adherence to these laws in the context of faceless corporations on one hand and allowing individuals to exercise free association on the other. The precedent recognizing corporations as persons is over a century old, and there is no indication in sight that our legal system is even considering such a reform. This further bolsters the position that both our legal system and the Constitution are irredeemable.

See “Pornography and the Failure of the Constitution”

Any person who baits cats for pit bulls or publishes text, photos, or videos excusing or condoning it, or offering it as a sort of torture porn sadistic thrill, should be made to know what true pain and horror is, through the brunt of the state and after a fair trial with due process, of course. Captain Byron Hadley has the right touch.