Correcting Common Errors in Pronoun Usage:

Another Foray in the Seemingly Lost Language Wars

One disconcerting but noticeable trend in public discourse over many years now is the propensity by far too many to use both first and third person pronouns improperly. Moreover, many mistakenly believe such errors are in accordance with otherwise correct admonitions by the increasingly few grammarians deserving to be called such. What on earth, some readers may ask, does that mean? Far too many, including many who make a living writing and speaking, utter grammatical abominations such as “between him and I,” “someone asked Douglas and I,” or even “there was a disagreement between he and Brian.” These sorts of mistakes, increasingly common not just in private discourse but in untold numbers of what is presented as media by paid professionals, call for a primer on correct pronoun usage as well as an explanation or theory on why this is happening. Apologies are extended to what is hopefully the overwhelming number of readers of this publication who do indeed possess a minimum level of erudition: a level of erudition that more than suffices as at least some minimum semblance of a classical education that has become ever more elusive in this vulgar age. These grammmar rules should have been learned at about the seventh grade. Such apologies notwithstanding, hopefully those who do possess a mastery of grammar and usage will find this primer an indispensable resource when such errors are encountered in both private and public discourse. Correcting bad grammar is almost as much fun as being bad in various devilish, decadent ways, but with the added benefit that it is simply the right thing to do. Europe and the West need grammar nazis more than ever. Indeed, the descriptivist scourge has apparently deemed utterances such as “between him and I” as acceptable, as demonstrated in a particularly contemptible entry in the Merriam-Webster website, as well as this entry in the F.A.Q. section of the r/grammar subreddit. The latter, quite incredibly, asserts that “both versions [“between you and me” and “between you and I”] are grammatical, but the me version will be overwhelmingly preferred in edited prose meant for publication.” This essay serves to contradict such an outrageous and destructive affront to basic standards in grammar and usage, while also offering a concise explanation of the grammar rules at issue.

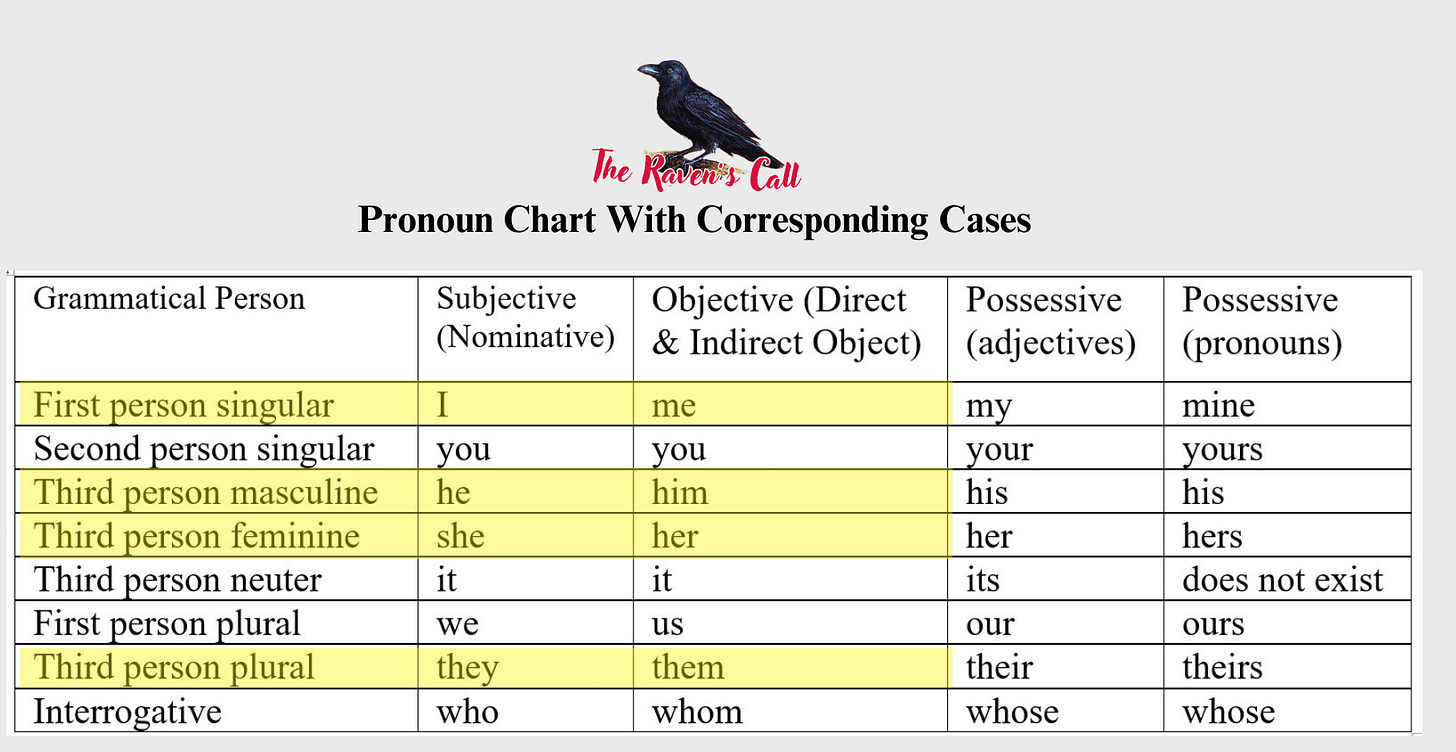

Dispelling such errors requires an understanding of the basic mechanics of nouns, pronouns, and what is known as “grammatical case,”1 hereinafter referred to simply as “case.” Case is simply the relationship that a pronoun has with other elements in a sentence, notably whether a pronoun is a subject, or direct or indirect object, or if a pronoun is possessive. The subject of a sentence, i.e. the noun or pronoun that is modifying the verb, is also known as being in the “nominative” case. Both a direct and indirect object are also known as “objective.”2 Possessive is also known as “genitive.” However, because these problems never seem to entail instances of the possessive, this discussion will be limited to the differences between the first two cases, nominative and objective. This table sets forth each pronoun as they exist in these three different cases.

Note that only the entries for first and third person singular, masculine and feminine, and interrogative pronouns are highlighted. Plural and second person pronouns are not highlighted because they never come into play with this controversy, either because “you” is the same in both cases at issue, and because no one ever says (or writes) “between him and we” or “between him and they.” Possessive pronouns and adjectives are included in order to provide a comprehensive pronoun chart, but have no bearing on this discussion.

In relation to these appalling errors heard with ever increasing frequency, not just in private discourse but by those who are (somehow) paid to write and speak for a living, the problem can simply be distilled as follows. “I” should only be used when the noun that pronoun stands for is the subject of the sentence. Similarly, “he” and “she” should only be used when those pronouns are the subject of the sentence. One helpful tip that should assist those wanting to disabuse themselves of such errors is that anytime a preposition (connecting words such as “between,” “against,” “to,” and so on) modifies a pronoun, or when any verb other than “to be” modifies a pronoun (e.g. “She hit it” or “He read it out loud to him) that pronoun is never in the nominative, i.e. is never the subject of the sentence. Therefore, the first- and third-person singular pronouns at issue (I/me, he/him and she/her) are NEVER “I,” “he,” or “she” when modified by a preposition or a verb other than “to be.” Another tip: use “I” and “he” and “she” where “we” and “they” sound natural, and use “me” and “him or her” when “us” sounds natural. The same rules also govern interrogative pronouns “who” and “whom.” Compare “who went to the market” with “to whom this may concern.”

A most interesting question concerns how these errors became so pervasive, and how is it that those who utter these mistakes falsely believe they are in accordance with the stern admonitions from the ever-diminishing number of grammarians in our ranks? The answer lies in two related errors that were more common, which grammarians corrected, but either did so with a less than comprehensive explanation, or, more likely, were poorly understood by far too many. An important property of the nominative case (subject) is that it pertains to both “sides” of “to be” verbs, e.g. “I am he” rather than “I am him.” This is why those who strive to speak and write properly will respond to “Is this Richard Parker?” not by stating “That’s me” or “this is me” but “I am he,” in the same way this could be answered “I (not me) am Richard Parker.” Bryan Garner is dismissive of that rule, calling it “frippery,” but those who speak German or made any effort to learn even rudimentary German know that this important rule is widely acknowledged and is also idiomatic in German, and that strict adherence to the rule in grade school in the Anglosphere would have avoided some of the confusion discussed below.

The failure of the ranks of English teachers since the 70s, hardly deserving of such a moniker at all, is the cause of a closely related error in pronoun usage, one which further explains some of these pronoun errors in a different context. That error relates to case error in comparative sentences consisting of “than” and “as;” pronouns modified by “as” and “than” generally, but not always, take the nominative case as well. The sentences “He is not as good of a player as me” or “He thinks that he is smarter than me” are wrong. They should read “…not as good of a player as I” and “smarter than I,” respectively. Why is this so? It is because both sentences imply the verb “to be,” which always invokes the nominative, not the objective, e.g. “This is I” or “It is I who held you to account for your abject irresponsibility on this matter.” The implication of the verb “to be” is implied in most (but not all) instances of comparative sentences with “than,” as evinced in how these thoughts might be expressed more fully, particularly in formal speech and writing; “He thinks that he is smarter than I am.” Caution is advised however because, although such utterances are rare, it is possible that comparative sentences using “than” and “as” can invoke the objective case. Example: “she is a lot nicer to him than I” is wrong. The proper case is “me” and not “I,” i.e. “She is a lot nicer to him than she is to me,”” as evidenced by the preposition “to” in relation to “him.” “She” is the subject of the sentence, thus taking the subjective case, the two individuals she is either nice to or not so nice to are indirect objects, “him” and “me.” The same principal applies to comparative “than” sentences implying a verb, except of course “to be” verbs. E.g., “She likes him much more than me,” which could also be written as “She likes him more than she likes me.” The same applies to sentences such as “He likes him as well as me.”

Confusion and persistent errors in relation to using the objective case for these comparative sentences, particularly in the late 80s and even early 90s prompted grammarians to correct the masses, admonishing that “me” is improper, “I” is the correct case, as these defenders of grammar and proper usage also corrected the use of “me” in sentences using “to be,” such as “It is I,” and not “it is me.” They made similar efforts concerning proper case in comparative sentences described above. Most grammarians doubtlessly took sufficient care to explain these nuances, but far too many took these corrections to simply mean that people should say “I” rather than “me,” regardless of the actual case that properly governs the use of first-person and even third person pronouns in any given instance. Merriam-Webster calls this “hyper-correction;” those more enlightened are not so kind, as an egregious faux-pas can never be any sort of “correction.” The result is beauty pageant contestants, Hollywood strumpets (this author recalls Pamela Anderson uttering “I” constantly in the objective case, stupidly thinking this makes her sound smart) making these errors more often than not. Indeed, a wide range of media personalities and even writers and public speakers are making these errors with increasing frequency.

It is hoped most readers have mastery of these important grammatical concepts. But in addition to explaining these important rules to those who make such mistakes and want to do better, this brief primer was composed with the additional intention to benefit even the most erudite, by explaining familiar concepts in a unique but concise way that will aid in their efforts to correct those who make such errors, while also serving as a useful resource that the erudite can use to help educate others who want to improve their speech and writing.

Regardless of education level, it behooves everyone to think about grammar with greater deliberation. Grammar can be a difficult thing. Indeed, sometimes both the subjective and objective cases can be correct, as demonstrated in a personal anecdote. One English teacher during my senior year of high school (one who played an important role in my turn around as a “late-bloomer”) admonished an attempt to correct what I wrongly perceived to be a grammatical error in the title of the film Roger and Me (shudder to think Michael Moore actually made a decent documentary once upon a time). “The film title is wrong,” I declared. It should be “Roger and I,” I confidently but mistakenly asserted. Her retort: “how do you know?” She correctly explained that the title could imply Roger and I (Michael Moore) as subjects, but it could just as easily imply the objective, such as a film not about “Roger and I,” but “Roger and me.”

Mastery of the rules of grammar and their precise application is needed now more than ever, as evinced by the sorts of descriptivist elements alluded to earlier, asserting that improper usage such as “between him and I” is (somehow) “grammatical.” The Merriam-Webster entry alluded to earlier is a particularly nasty example of the descriptivist mindset, mocking and belittling those who care about proper grammar usage as so “many angry people on Twitter;” the entry complains, in a rather condescending tone, that “there are people out there who take grave exception to this particular turn of phrase, and they are very angry when they hear it.” The screed sanctions such egregious grammatical errors by quoting a prior usage guide:

You are probably safe in retaining between you and I in your casual speech, if it exists there naturally, and you would be true to life in placing it in the mouths of fictional characters.3

This is exacerbated by the audacious quip “no doubt that our language will occasionally assimilate incorrect usage, and over the course of time, come to accept it, if only begrudgingly and slowly.” The rapid “assimilat[ion of] incorrect usage” only occurs because nefarious institutions, like Merriam-Webster, sanction even the most egregious errors, creating a feedback loop that sanctions and normalizes these sorts of errors, which then bolsters and encourages a critical mass of the public to not bother with mastering basic rules of grammar at all. In this way, instructive essays like this one serve an even greater purpose, especially for those who do know these rules and apply them flawlessly; restating and reiterating these basic rules contradicts these destructive elements of descriptivism in language and culture that, unfortunately, enjoy such institutional backing as to render them nigh invincible. Aber wir ziehen in die Schlacht trotzdem.

A SPECIAL NOTE, particularly for new subscribers and those unacquainted with this publication. This essay is featured in a special section entitled “Matters of Language.” Those readers concerned about the devolution and degradation of not just the English language but European and world languages generally are encouraged to peruse that section. The flagship essay or treatise “Descriptivism Defied: In Defense of Prescriptivism in the Language Wars” is highly recommend in particular. Readers will also find essays on other important topics, including an essay “On the Misuse and Abuse of the Word ‘Literally:’ Against This Most Vexing Blather” and a two part series attacking the preposterous notion of customizable pronouns to advance the transgender and radical gender causes and how those interests have attempted to redefine the word “gender,” while insisting this word has always signified the redefinition they advocate for.

Those readers who find this content particularly insightful and beneficial are urged to consider a paid subscription, or even pledge their support as a “founding member.”

Follow Richard Parker on twitter (or X if one prefers) under the handle (@)astheravencalls. Delete the parentheses, which were added to prevent interference with Substack’s own internal handle system.

Because this primer only concerns grammatical case error and pronouns, only pronouns will be referenced going forward. This is because English, unlike like German, French, Spanish and other language with gendered definitive articles presents no possibility of case error with nouns.

Sometimes this is referred to by students of German as a foreign language as “accusative,” although this is imprecise because accusative only pertains to direct objects, while English does not have the “dative” case as a form exhibited in the German and other languages.

This author of course condemns the usage of the second person in any sort of formal writing, which should certainly include any commentary or guides on grammar usage, no matter how destructive and harmful they may be, such that one can hardly refer to such fetid, putrid excrement as any sort of commentary or instruction on grammar as the term is properly understood. To think these people are educated and consider themselves as such is yet further testament to the fallen state of higher education in Europe and the West.

Hey Richard, great article— I love that you address these annoying, flippant issues plaguing our discourse. It’s all part of the decadence relentlessly consuming us…

If people don’t stop using myself wrong, it’s going to bring about the apocalypse.