Living Young in "Good Old 1955"

Reflections on Themes of Culture, Youth, and Destiny in Back to the Future

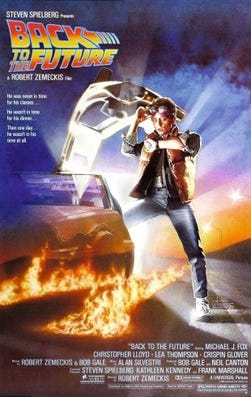

As entertaining as it is profound, Back to the Future enjoys truly universal acclaim. Even after almost forty years since its release, the film continues to captivate audiences, and not without very good reason. However, two noteworthy aspects of the film seem to have received little notice from much if not all of the public discourse on the film; namely the degree to which the film demonstrates that people are a product of the time, circumstance, and cultural milieu they were born into, as well as how adolescence and young adulthood are the most important times in one’s life, a period of time where more opportunities are typically availed to the individual than later in life.

“Thrust Into It All; The Individual Defined by Culture and Circumstance” discusses at length the incalculable degree to which what most regard as individual autonomy and individual choice is profoundly affected by the time, circumstance, and cultural milieu any given person is born into. In Sein und Zeit, Martin Heidegger coined the term Geworfenheit, which, while commonly translated as “thrownness.” is perhaps better translated by this author as “the state of being thrown or thrust into.” This concept explains how the individual is born into any number of external circumstances he is thrust into, from the time and place he was born into, to the religion and mother tongue he will inherit by virtue of such circumstance, to any number of externalities that will envelop him, most particularly the mores, customs, and cultural milieu he is immersed in. This important concept remains alien to much of our Anglo-American tradition but is nonetheless key to understanding the human nature as it actually exists.

The manner in which Back to the Future exemplifies the phenomenon of Geworfenheit is something that I have reflected on quite a bit, both before, during, and especially after my most recent viewing. As Back to the Future is set in 1985 (almost forty years ago), the viewer beholds the principles of Geworfenheit as he observes the manner of dress, music preferences, and other cultural expressions seen in Marty McFly and his surroundings as he wakes up late for school and goes about his morning and day. A viewer notes the aerobics class so typical of the 80s he passes on his way to school, the cars people drive, and other visual clues that this was 1985. Unlike some movies from this period, nothing seems that drastically dated to 1985, although again there are signs and tells that Marty and everyone around him are a product of the time and circumstance they find themselves in, as all individuals axiomatically are.

In the second act, Marty goes to meet Doc Brown at the Twin Pines Mall to film his presentation before his intended time travel. This was soon interdicted by Iranian terrorists whom Doc Brown swindled to procure nuclear plutonium to power the time machine. After Doc Brown was seemingly shot and killed, Marty flees in the DeLorean as the terrorists give chase with automatic weapons fire, accelerating until the speedometer hits 88mph, and in an instant he travels back in time to 1955. It is then that the more astute viewers can behold what an incalculable effect the time, circumstance, and cultural milieu has on how any individual is formed and what choices that individual makes, as the viewer discerns how everyone Marty encounters is so peculiar to that time.

The morning after, Marty meanders about in Hill Valley as it was (or is) in 1955. Men wear suits of the time period, replete with hats, as cars of the period pass by. The service station offers full service in a way that was only offered in that period of time. Of course, he then walks into a malt shop with “The Ballad of Davey Crocket” playing in the background, yet another conspicuous auspice of that cultural milieu and time, before bumping into his father, George, as an adolescent. As before, everyone Marty interacts with is a striking reminder of where and when he finds himself.

While all of the peers of George, Lorraine, and Biff are peculiar to the youth culture of the time, one of Biff’s cronies is particularly illustrative of this principle. This ne’er-do-well wears 3-D glasses seemingly wherever he goes, an utterly absurd style choice unless one is viewing 3-D movies on a constant basis, or one is a youngster in 1955 in America when this was a cultural trend in young fashion. Does he truly choose to wear such attire, attire that would be absurd to any young person of any other generation and period of time, or does he wear the 3-D glasses out of a limited choice, one of many things made available to him by the time, circumstance, and cultural milieu that envelops him, not unlike a drop-down menu in which the choices available are populated by these external factors.

The attire and mannerisms of young Lorraine are equally illustrative of this principle. Even if one were to have never seen Back to the Future and were shown, out of context, the scene of her at high school, or the malt shop, or the scene where she follows “Calvin Klein” to Doc Brown’s home, her manner of dress, hairstyle, and other visual cues would instantly inform such a viewer that she is a teenage gal in the 50s. When one observes her in the scenes at the high school or malt shop, it is remarkable how similar her attire and mannerism are to her peers. So very often, people are far less individualistic than our Anglo-American tradition supposes and are much more like a school of fish.

Quite famously, these same propensities are exhibited in the famous scene where Marty must stand-in for lead guitar after Marvin Berry injured his hand, to ensure that George kisses Lorraine at the Enchantment Under the Sea dance, lest Marty too is erased from existence. Lorraine, George, and their peers react most enthusiastically to the rendition of “Johnny B Goode,” as it was a number that, while novel for the time, still nonetheless drew heavily from the music of the youth culture at the time. But to a man—like a school of fish—they scoffed at the heavy metal solo riff at the end. This same riff that was so untenable to those kids in 1955 would be and was popular among many in 1985 precisely because of how the cultural milieu that envelops the individual shapes him to such an incalculable degree. Take any of George and Lorraine’s peers and have them born not in 1938 but 1968, and a large number of them would have loved that solo heavy metal guitar riff. In this way, whether someone likes Marty’s heavy metal guitar guitar riff is far more dependent on when and where he was born than any one individual’s unique predilections.

◊

Another aspect to Back to the Future that seems to receive far too little attention is what it says about youth and middle age. Of course, time travel is impossible. What we see of Marty’s family and his parents in particular at the family dinner on the evening of October 26, 1985 is distressing. George is a pathetic pushover who laughs like an idiot at old Honeymooner episodes after suffering abject humiliation from Biff in his own home. Lorraine has lost her beauty, drinks and smokes to excess, and thus is overweight. When the viewer learns that Marty’s uncle will not be paroled, the metaphor, likening Lorraine’s life to a prison sentence, is unmistakable. After the homely daughter, Linda, makes a snide comment about her uncle, the camera catches Lorraine glaring at her husband with contempt, lamenting “We all make mistakes in life, children.” A moment later, Lorraine recounts how she and George first kissed. And she says with a look of utter despair “It was then I realized I was going to spend the rest of my life with [your father].” Utterly oblivious to what is most obvious to the viewer, George laughs in that guffawing manner at a rerun of a sitcom he has doubtlessly seen countless times before, shaking his head and slapping the table.

At 47. no real options are available to Lorraine, certainly not the options she had as such a fetching, comely lass of 17 when the viewer sees her in 1955, thirty years prior. She can either choose to stay with her husband and her kids, an existence she can only muddle through with strong drink, or what? Setting aside the obligations she has a mother and by virtue of her marital vows to her husband, what man would have Lorraine at that state at 47, alcoholic, chain smoking, overweight, with three children in adulthood and late adolescence? Because time travel is not possible, more discerning viewers will discern that the greatest opportunities will be afforded in youth, and that the choices one makes will determine that person’s destiny in profound and at times truly horrifying ways. No one has or will ever have Doc Brown’s time machine.

A most interesting topic, and one that does not seem mentioned enough or at all in the public discourse around this celebrated film. The same considerations of course apply to George. Through the device of time travel, the viewer discerns that by choosing to stand up to Biff, his destiny would take an infinitely brighter destiny than what was shown to have happened before Marty’s time travel interfered with the original timeline. One interesting question, and one that is not addressed in anyway by the film, is what circumstances in George’s family or upbringing led him to behave so clownishly, that would make him a continual target for bullying? A weak father figure is the best guess, as Crispin Glover was seemingly handsome enough in his youth. In a way, Back to the Future is about a son who mentors his father, corrects the mistakes of the past and improves the destiny of both. Quite profound, but as stated it does not answer what put George on this terrible trajectory in the first place.

The viewer does get a glimpse of Lorraine’s family life, but nothing indicates why she was prone to drink other than run-of-the-mill teenage rebellion. The Florence Nightingale effect, whereby young a lady becomes infatuated with an injured young man she acts as caretaker for seems much less of a risk for life ruination categorically, and so it seems much of her original fate was attributable to bad luck in that it was hapless George who was hit by a car and under her care. One should of course take caution against smoking and drinking to excess to heart. But to the extent that selecting George is a mistake or not (depending on which version of him she chooses) should viewers discern that young women need to be more discerning about love interests, rejecting a young man with George’s problems categorically? Or is it possible for a love interest like Lorraine to give a young man the strength and fortitude to assert himself and improve himself in ways that would make him more worthy of such a catch? Was Lorraine’s father somehow wanting as a role model or father figure? These and other questions are never answered.

One is loath to mention either of the sequels, but, in relation to this particular subject, an ending line by Doc Brown in Part III needs to be addressed:

It means your future hasn't been written yet. No one's has. Your future is whatever you make it. So make it a good one, both of you.

This is feel-good pablum. Perhaps it is true to an extent, depending on the time in one’s life and overall circumstance, but on the evening before Marty goes back in time, it is clear that both Lorraine and George are trapped in the circumstances of their middle age, in which mistakes of varying degrees of gravity led them down a horrible path to mediocrity, failure, and despair. The future of Lorraine in 1955 had not yet been written, the present and future of Lorraine in 1985 before Marty goes back has been set in stone. And while young George in 1955 was already well down a very bad trajectory, that was overcome by good fortune and a key decision at just right the time in his youth, by way of interdiction from his son from the future, who came back to 1955 in a time machine that could never exist and never will exist. This fact, that no one will ever be able to do as Marty did, means that young people need to understand how important that period of life and that young people need good mentors in their lives to help them avoid these and other mistakes; young people like George need to get right the first time around because there are no second chances. Despite the Hollywood feel-good reassurances offered at the end of a regrettable set of sequels, a truth about the nature of the stages of life is nonetheless revealed in the true classic of the series and the only installment worthy of discussion and analysis.

Whatever misgivings one may rightly have about Hollywood or even some of the players involved in this film, Back to the Future is, quite obviously, a timeless classic. Very few films are so universally loved. That it reveals truths about philosophical principles such as the profound, defining effect the time and cultural milieu one was born into as well as insight about how choices made in one’s youth can lead to both positive and negative trajectories is a testament to its staying power not just as cinema but as a work of art. It is a timeless favorite for good reason, and however much culture has devolved in such spectacular fashion over the decades, high points like this film offer a much needed, vital respite from so much of the dregs of American popular culture.