Big Fan: A Study of the Pitiful

An Analysis and Review of The 2009 Film Big Fan

Meet Paul Aufiero, a little man in a little box. AUTHOR’S NOTE: there are SPOILERS in this review pertaining to the first thirty to forty minutes of this film.

As another NFL season will be upon us shortly, this review and analysis of Big Fan (2009) seems timely. While many would, with very good reason, preclude anything with Patton Oswalt from consideration, casting him in this particular film works incredibly well, probably because to a large extent he plays himself. Written and directed by Robert Siegel, the movie concerns a devout, obsessive New York Giants fan, Paul Aufiero. He lives on Staten Island with his mother, while working as a parking garage attendant late at night. He calls into at least one late night sports talk radio show, most particularly “Sports Dogg,” voiced by real-life sports talk personality Scott Farrell. An even stranger friend, Sal, who looks up to Paul for whatever reason, listens to his friend’s sports-talk call-ins and actually admires his poorly articulated, cliched rants.

The plot of the film is very simple. While having pizza together with his friend, Sal spots star linebacker and linchpin of the Giants’ defense, Quantrell Bishop and a small entourage of friends at a gas station across the way. Wanting to meet their favorite player, the two fans follow Bishop’s SUV. Bishop and his group first stop at a run-down house in Stapleton, further indicating that a drug deal was underway, something that escapes the two fans. Paul and Sal then follow the SUV into Manhattan, which leads them to a somewhat upscale strip club near Times Square and the Theater District.

Paul and Sal sit, staking out their favorite player, utterly uninterested in the almost nude women around them.

Sitting across and at some distance from Bishop and his friends, Paul and Sal are shown hesitating for some time on how they should approach Bishop. At one moment during this scene, the men are approached by a half-naked stripper, who sits first on Paul’s lap and then Sal’s, trying to proposition a lap dance. Neither is at all interested, and are actually annoyed at the woman because she is interfering in their surveillance of their idol: a less than subtle cue by the filmmaker that there is something so off about these two that they do not respond to sexual stimuli that is effectively hard wired into normal, healthy men, even those who rightly eschew or are otherwise averse to strip joints out of principle. Further underscoring how socially inept these two are, Sal suggests to Paul that he follow Bishop into the men’s room and try starting a conversation while relieving themselves. “It would be casual, just two guys, pissing and chatting,” Sal reassures him. We see Paul follow Bishop and one of his friends into the bathroom and lurk briefly, but Bishop went in there to fix his hair and freshen up as they talk about one of the women “with the Brazilian bubble butt.” The hapless fan hesitates in the midst of a very bad idea, and very quickly Bishop and his friend walk past the two.

Sal’s very foolish proposal is the infamous urinal meme depicted in live-action cinema, at least as conceptualized.

To describe this decision as wise or correct is questionable, because none of these ideas are good or sensible decisions. That he made the least dumb decision is not enough to save Paul from the disaster that soon follows. Sometime after aborting any “conversation starter” in the men’s room, and after Bishop refuses a drink the two bought him (which they cannot afford), Paul walks up to the table where Bishop and his entourage are seated, and then introduces himself as a “big fan” that wanted to say hello, with Sal following close behind. At first, Bishop and his entourage are receptive. “Look at this mother-fucker, dawg,” one of his friends proclaims. A friendly exchange is had, but only for a few, fleeting seconds. For just as Sal (unwisely) tells “QB” and his circle that they are from Staten Island, Paul mentions the “stop in Stapleton.” Bishop quickly realizes that Paul followed them from Staten Island. Bishop gets irate, quickly loses control, and, just before the word “stalker” is heard amongst a fusillade of profanities, pommels the fat schlub mercilessly, putting him into the hospital with a concussion, a hematoma (collection of blood in the skull). As a result of the beating, Paul was unconscious in the hospital for three days. Once informed by the attending nurse of his condition and that he will have to stay a few days for observation, and learning that “today is Monday,” the first question Paul asks is “How’d we do?”

Much of the rest of the film concerns the dilemma Paul is faced with in the aftermath. Bishop’s assault makes national news and is the focus of sports coverage of both the New York Giants and the National Football League over several weeks. The district attorney wants to charge Bishop for felony assault, but cannot unless Paul agrees to cooperate. Because of the pending charges that hinge on Paul’s decision, Bishop is suspended indefinitely on a week-to-week basis, and the Giants, who had started very strong through midseason at 9-2 at the beginning of the film, suffer a losing streak as a result, placing their bid for the playoffs and even a Super Bowl championship in jeopardy. Paul has a decision to make. He can press charges and sue Bishop for damages arising from an intentional tort. This would benefit him materially and, most would agree, salvage some small vestige of his dignity. But this decision would directly harm the one and only thing he loves and cares about: The New York Giants. Not only would that ruin this season, but it would hamper the Giants’ prospects for the foreseeable future. The alternative decision is not to press charges, not pursue civil damages, sacrificing material gain and, most would argue, his dignity and self-respect, but this decision would help his team, or at least refrain from taking action that would harm the Giants that season and beyond.

Paul in his parking attendant booth. The metaphor of this box as a cage, especially with the chain-link lattice work over the window could not be more obvious.

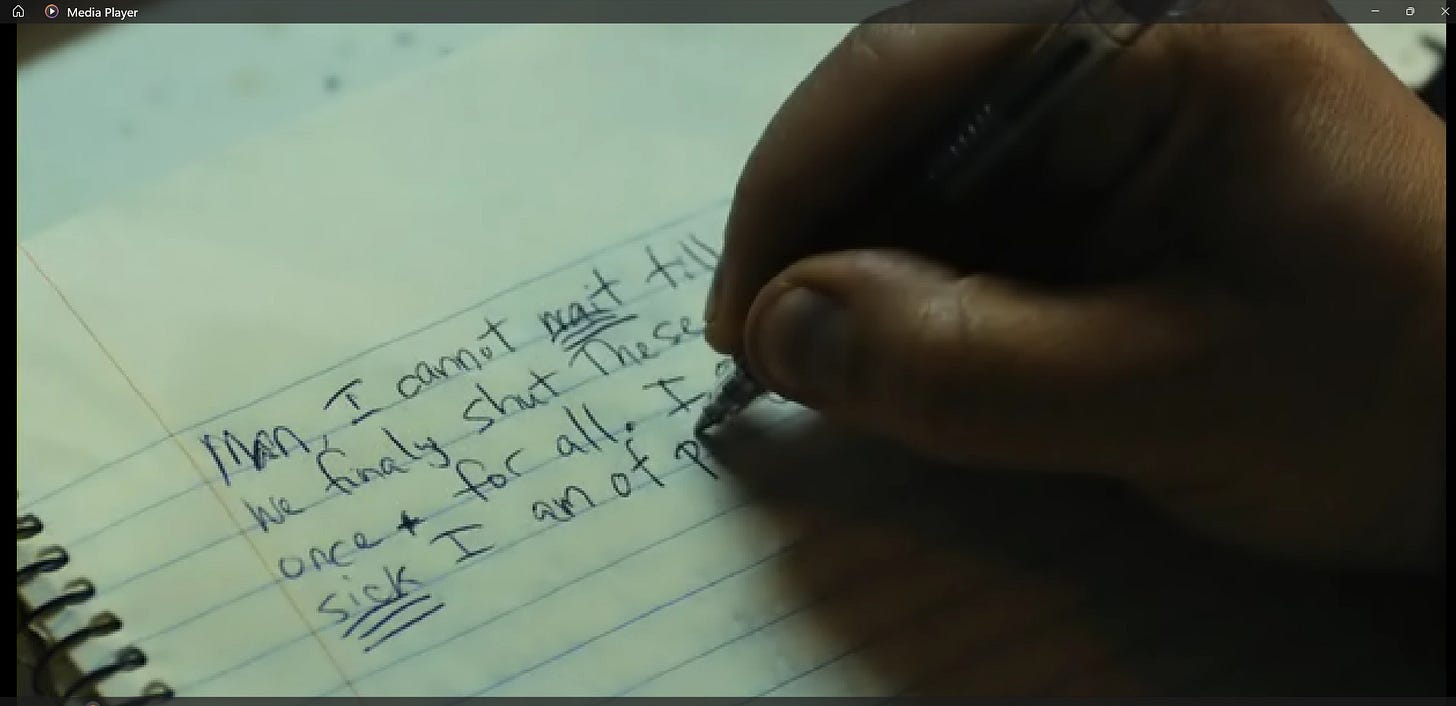

This review will refrain from divulging what Paul decides to do in the end. The spoilers above are minor and all happen within the first thirty minutes of the film[1], setting up the dilemma faced by Paul that unfolds over the next hour or so. To describe Paul as a pathetic, loathsome character is an understatement. The opening shot, showing Paul confined in a parking lot attendant both, trying to mouth out his prepared rant over a late-night sports talk radio call-in show, stating “I cannot tell you how sick I am” twice could not be more overt. Both the confining parking lot attendant booth as a metaphor and the line “I cannot tell you how sick I am” inform so very much about Paul in the opening seconds of the film. As he tries to put together one of the most worn out, tired refrains in the English language, the viewer hears him saying aloud the diatribe he stodgily composes. A screenshot of his handwriting looks like it could be written by a child, suggesting both a deficiency in intelligence and education, and possibly some sort of stunted personal development as well. None of his commentary on “Sports Dogg” reveals any real insight into the game or his team, consisting of a lot of off-the-shelf cliches that comprise most of the blather heard on sports talk radio and even a lot of presentations on network and cable television.

A close-up of the fan’s hand-writing, in preparation for one of his lame calls to “Sports Dogg.”

A recurring theme in the movie, providing much needed comic relief, is that his mother invariably hears his calls late at night, before she admonishes him through the walls to be quiet. The viewer also learns of Paul’s masturbatory habits, both by depicting such under a blanket (thank god more was not shown) and during a hilarious but disturbing altercation with his mother. His room, filled with cheap sports memorabilia, looks like that of a child or at best very early adolescent. And because there is no suggestion of a pornographic magazine or video or any physical sign or cue that Paul takes any interest in women at all, it is uncertain if Paul even thinks about women while tending to himself, or if he is thinking about what is shown to be his undying obsession in all other contexts: the New York Giants and the largely if not exclusively black roster of athletes that play for them. Stunted development is further depicted in the various scenes showing Paul, a middle-aged man living with his mother, covering himself with an NFL-themed blanket for children and maybe young adolescents. Perhaps most disturbing of all, one scene soon after the beating shows Paul looking at his Bishop jersey, only to then put the garment on over his underwear, before curling up in a fetal position. He not only wears a jersey emblazoned with the name of man who severely beat him, he wears this jersey like some women wear a man’s shirt as a nightie.

Paul and his NFL blankie. On the left, he is seen after the beating. Above him is a poster of the man who beat him so severely. On the right, Paul covers his face during an argument with the family.

It is also interesting that no one would ever describe either Paul or Sal as “rabid” fans. They are beyond emotionally invested in the New York Giants, but both are the inversion of a certain archetypal fan who is masculine, intimidating, and fanatical. While many would argue their fixation on a sports team is misguided at best, many fans do take an interest in women, and do carry a certain presence. As much as Americans like to disparage soccer, the typical ultra-fan in Germany and Europe is certainly not the sort to be trifled with. Paul and Sal are the very negation of such misguided masculinity.

Pictures of unrest from a match between Dresden Dynamo and Eintracht Frankfurt. Pictured are some of Dresden’s Ultra Fans, very much the opposite of what Paul and Sal represent.

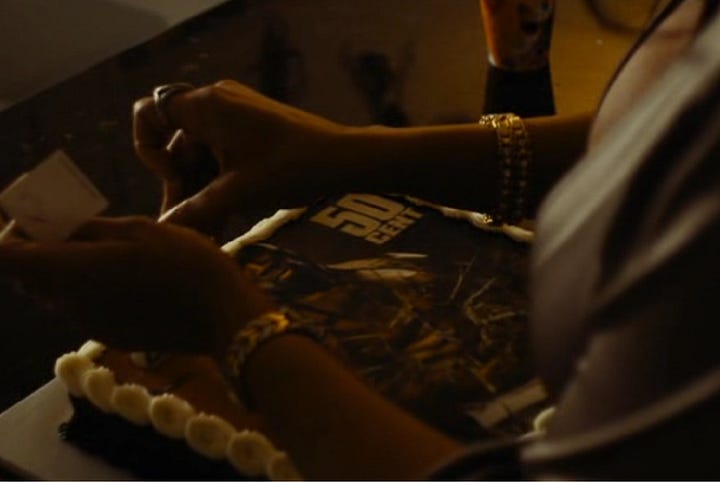

There are other details in the film that portray the very vulgar picture that is modern America. An early scene in the film depicts a birthday party for Paul’s nephew. His sister-in-law, a trashy bimbo with ridiculously large, fake breasts, excessive tan and gaudy makeup, greets Paul and his mother at the door, before preparing and then presenting her seven-year-old son with a “50 Cent” themed birthday cake. Later, Paul’s brother, a plaintiff’s attorney, auditions a low rent television advertisement, the sort one might see late at night on local network television. Another detail is Paul’s habit of pouring granulated sugar into a glass of Coca-Cola.

Paint a vulgar picture. The birthday scene offers a lot of nice details, including the appearance of Paul’s sister-in-law, and the 50-cent themed birthday cake.

For those who denounce the NFL and “sportsball” generally as bread and circuses that distract and anesthetize fans from the societal and personal problems that plague them and our civilization, Big Fan provides a searing rebuke of sports fandom generally and the average NFL fan in particular. There are doubtlessly many who support a beloved team, but do so with increasing reservations about what the NFL stands for. For those fans in such a dilemma, the film presents hard, difficult questions that are not easy to answer. How similar is a passionate football fan (or a fan of a particular team) to a loser like Paul? What makes a given fan different from Paul? What would a star player have to do to someone for that fan to no longer care if that team wins or loses? One would hope, if nothing else, this image would help dissuade adult fans from wearing jerseys with other men’s names on them.

Paul lying in a fetal position, wearing his underwear and a jersey emblazoned with the name of the man who beat the shit out of him, with the poster of Quantrell Bishop still hanging on his wall. Some women wear such garments as a nightie. If attractive, that can be a very alluring but informal look. The most grotesque antithesis of that vision comes in the form of an ugly, overweight, likely autistic man wearing the same.

Many might disagree, but Paul is not entirely loathsome. Whatever decision he ultimately comes to by the end of the film, the fact he is hesitant at all to press criminal charges or even pursue civil damages reveals a certain quality of character that some may describe as implacable. That can be an incredible attribute, or it can be the very worst sort of fault, depending on what it is a person is so adamant about. Most would agree it is a personal failure in Paul’s particular instance, but then again, just as “how could a billion Chinese be wrong” used to be a popular adage, there are tens of millions of NFL fans with similar levels of passion.

Very much for the worse, the NFL is bigger than it has ever been. This is true even though it continually dilutes the quality of the product in a number of different ways. The League has expanded the season from a sixteen to seventeen (soon to be eighteen) game season, while pairing the preseason from four games to three. The contraction of the pre-season has resulted in teams looking off the first few games of the season. The League has also added a seventh seed to the playoffs, making regular season games count for far less; it used to be hard to get into the playoffs. The quality is further tainted by Thursday night games, which simply do not provide enough rest from the prior Sunday (Thursday Night Games are notoriously prone to be stinkers). The NFL has further expanded abroad, first into London, now Germany and Mexico, and this year Brazil. Teams that go to Germany or London perform abysmally the next week, provided they do not take a bye week after. That trend is so strong, Las Vegas bookies set odds and NFL columnists pick games to it.

Two memes reflecting the cross-contamination of Taylor Swift and the NFL, which has been a thorn in the side of many traditional fans, with constant cutaways to Swift in the luxury box during Kansas City Chiefs games. Taylor Swift is of course an obsessive interest for a certain sort of white woman and even girls (as in teens and children).

Then there is the pariah of Taylor Swift attending all of the Chiefs games on account of her being with Travis Kelce, replete with constant cutaways to Taylor Swift in her booth to attract viewership not from football fans, but Taylor Swift fans. The integrity of the League is questionable in other ways, from questionable calls that have determined Conference championship games, including the notorious game in which the Cincinnati Bengals lost to the League’s new favorite, the Kansas City Chiefs, as well as the New Orleans Saints being deprived of a Super Bowl berth with a phantom pass interference call that placed the Los Angeles Rams against the Patriots, most suspicious indeed as that set up a much more favorable match up for Robert Kraft’s Patriots: just one of a long litany of bogus calls that favored the hated cheaters. Two cheating scandals, that we know of, by the Patriots were swept under the rug by commissioner Roger Goodell, who landed that most lucrative job at the behest of Patriots owner Robert Kraft. No conflict of interest there. This among other problems, including a crisis in competent officiating that has worsened over the past couple of years. This of course is on top of the pandering to Black Lives Matter and social justice issues that have arisen with the race riots of 2020, replete with the rebranding of the once storied Washington Redskins to the incredibly stupid name, Washington Commanders.

But despite these and many other drawbacks, fans still cling to football. This somewhat obscure movie offers a most unflattering look at such fandom, unwavering and unflinching in the ugly, pitiful portrayal it depicts. One could of course argue Paul Aufiero, as an incredibly grotesque figure, is an extreme outlier for football fans, almost bordering on parody. Whether viewers take a hardline stance against sportsball or retain loyalty to a particular team notwithstanding increasing reservations, this film raises very difficult and unpleasant questions, as it puts a mirror up to the most revolting and pathetic manifestations of fandom. While it is certainly not a masterpiece, this is an excellent film that is just as relevant today as it was fifteen years ago. Highly recommended.

[1] These plot points are also revealed in the trailer but so are many other things, arguably spoiling too much.

Sportsball is a rite in the Negro Worship Order of Wokeianity.